The earliest instances of villainous “mwahahaha” laughter in entertainment date back to online chatrooms around the early 2000s, particularly via IRC (Internet Relay Chat). However, the concept of evil laughter itself, central to villainy, is far older and deeply rooted in cultural and literary history.

The spellings “mwahaha,” “muahaha,” and their variants first appear in recorded texts near the year 2000. Google Ngram data indicates that “muahaha” and “mwahaha” gained popularity only after 2000, with “mwahaha” overtaking “muahaha” as the preferred form quickly. Early documented uses include a 2003 computer programming book referencing “muahaha,” and a 2003 text on villainy mentioning “mwahaha.” These written forms initially surfaced within IRC chats—early online group communications where users often conveyed tones or emotions through text mimicking vocal expressions.

Despite the recent origin of the specific “mwahaha” spelling, the notion of evil laughter as a hallmark of villainy is very ancient. Greek tragedies provide some of the oldest written examples. Scholars point out that in classical literature, villainous laughter is dark, malevolent, and mocking. In Sophocles’ Ajax, Athena asks whether laughing at enemies is the sweetest laughter. Similarly, Aeschylus’s Eumenides depicts the Furies expressing delight with a sinister laugh at human bloodshed. These instances establish malicious laughter as a tool of antagonists, meant to torment protagonists and signify evil intentions.

Philosophically, Plato viewed laughter negatively, describing it as a violent eruption that overrides reason and signals a loss of control. His interpretation frames laughter itself as potentially malignant, adding depth to the longstanding cultural suspicion toward “evil laughter.”

In later centuries, terminology to describe such villainous laughter emerged. The term “wicked laughter” was first attested in 1784, while “evil laughter” appears in records dating to 1860. These phrases captured the essential characteristic of villainous laughter: a marker of malicious intent and moral wrongdoing. Evil laughter illustrates a villain’s gratification from wrongdoing, positioning them clearly as the story’s antagonist.

Victorian and 19th-century operas and literature frequently featured evil laughter. Charles Gounod’s 1859 opera “Faust” has the villain Menistophenes punctuate an aria with sinister laughter. Ruggero Leoncavallo’s 1892 “Pagliacci” includes the character Canio laughing evilly before killing his wife. Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen” uses villainous laughter for Alberich, a key antagonist. Literary fairy tales, like those collected by the Brothers Grimm, also incorporate this trope in text form.

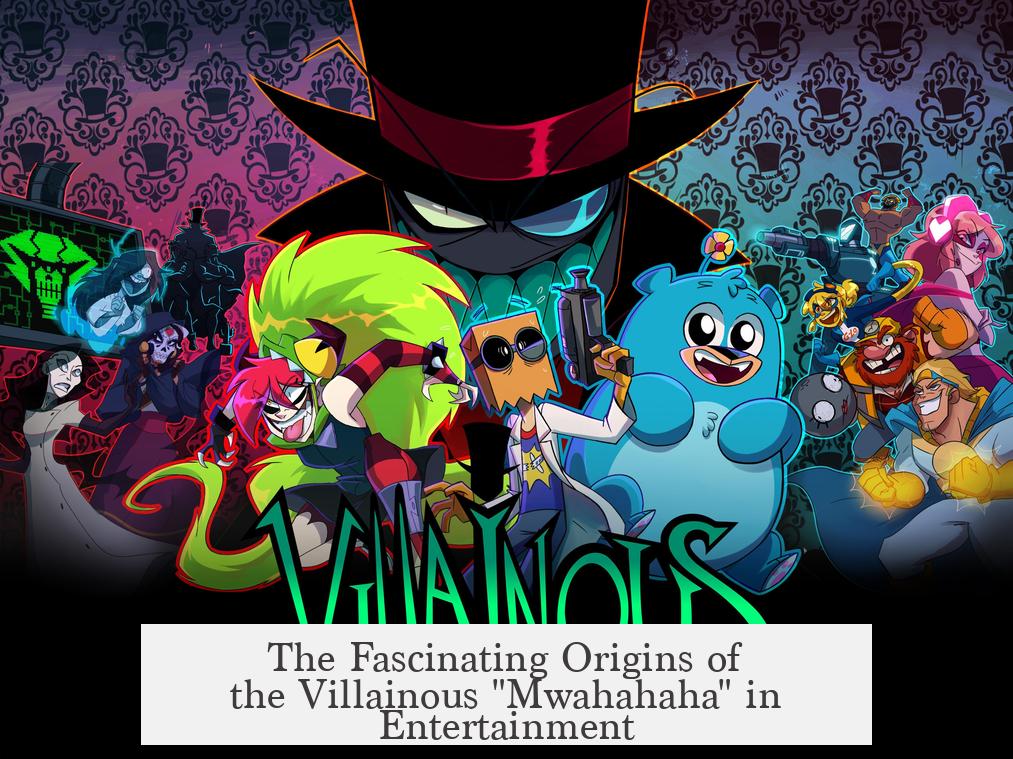

Early 20th-century cinema solidified the evil laugh as a recognizable villain cue. Notably, the Wicked Witch of the West in the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz” delivers one of the most iconic sinister laughs in film history. The 1937 “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” features the Evil Queen’s witch disguise transformation complete with an evil laugh, helping to cement this trope in popular culture.

Comics have also embraced villainous laughter. The Joker, debuting in “Batman #1” in 1940, famously cackles after acts of menace, such as pushing Batman off a bridge. The Joker’s laugh serves as a signature expression of his anarchic evil and madness.

Video games quickly adapted this trope too. In the 1985 game “Kung Fu,” villains would laugh remotely when players failed to defeat them. Since then, evil laughter has become a common and sometimes parodied motif in video games, movies, and television shows.

Summarizing:

- The specific spellings “mwahaha” and variants originated online around 2000, especially in IRC chats.

- The concept of villainous or evil laughter dates back to ancient Greek literature and philosophy.

- Terms like “wicked laughter” and “evil laughter” came into use from the late 18th to mid-19th centuries.

- 19th-century opera, theatre, and literature used evil laughter to mark villainy.

- Early films in the 1930s, especially “The Wizard of Oz” and “Snow White,” popularized the trope visually and auditorily.

- Comic books like Batman’s Joker further embedded the evil laugh in villain characterization.

- Video games adopted it in the 1980s, continuing to the present day.

Evil laughter remains a potent symbol of villainy, evolving from classical texts through various media to its modern digital and pop culture expressions.

The Fascinating Origins of the Villainous “Mwahahaha” in Entertainment

Ever wonder where that iconic villainous “mwahahaha” laugh originated? You know, the one that instantly screams, “I’m up to no good!” Right off the bat, the specific spellings like “mwahaha” or “muahaha” first showed up around the year 2000, mainly in early internet chatrooms and some quirky early 2000s books.

But hold on—while the typed “mwahaha” might be a newbie, the idea of the diabolical laugh itself goes way, way back, at least to ancient Greece. So, before computers even existed, villains were already chuckling their heads off in classic tragedies.

From Ancient Greece to Modern Chats: A Laughing Journey

Let’s peel back history a bit. In Plato’s Republic, which is no bedtime story, laughter isn’t just funny noise. Plato calls it a “malignant, violent paroxysm,” hinting that laughter is a sinister takeover of our reason by wild emotion. Hard to picture laughing villains without this dark philosophical stamp!

Greek tragedies offer the earliest written instances of evil laughter. Characters like the Furies in Aeschylus’ Eumenides revel in human misfortune, declaring, “The smell of human bloodshed makes me laugh.” Even Sophocles’ Ajax explores whether mocking enemies is the “sweetest laughter.” It’s clear: villainous laughter existed to taunt, intimidate, and mark moral failure.

The Birth of Wicked and Evil Laughter Terms

Fast forward a few centuries—literary thinkers started naming these laughs. “Wicked laughter” appears in texts as early as 1784, followed by “evil laughter” around 1860. These terms crystallized the trope, packaging the laugh as a behavioral signpost for villains.

Villainous Laughter Takes the Stage and Screen

The 19th century loves its drama, and so do villains! Opera and theater give us some famous early villains who use eerie laughter as a call sign. In Charles Gounod’s Faust (1859), a character’s laughter cuts through the aria. Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (1892) has Canio laugh evilly just before committing murder. Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen shows us Alberich, whose laughter rings clearly villainous.

Not just confined to opera, the Brothers Grimm toss in evil laughter too, like in their tale The Nix in the Mill-Pond. That swirling dark chuckle clearly fascinated storytellers long before the term “mwahaha” hit print.

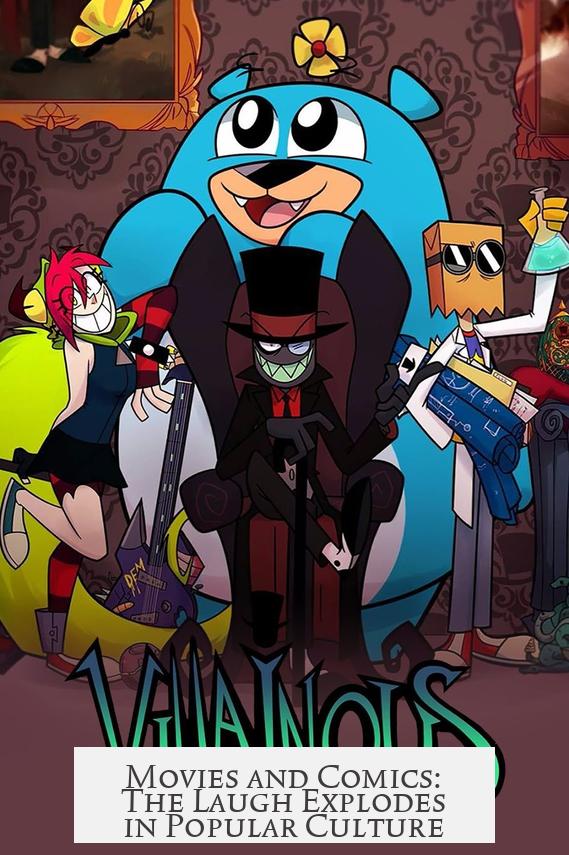

Movies and Comics: The Laugh Explodes in Popular Culture

Step into the 20th century, and you find villainous laughter taking the spotlight in movies. Remember the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz (1939)? Her cackle is so legendary it practically defines villainous laughter for generations. Before that, Disney’s Snow White (1937) shows the Evil Queen’s transformation punctuated by a chilling laugh.

Meanwhile, comics jump on the villain laugh bandwagon. The Joker debuts in Batman #1 in 1940, instantly establishing his menace with a haunting laugh after pushing Batman off a bridge: “Ha-ha-ha-ha!” Nowadays, you can’t think of the Joker without that grin and that eerie, infectious laugh.

When Video Games Joined the Laugh Parade

By the 1980s, video games adopted the trope, making villains laugh off-screen especially when the player failed. Notably, the 1985 game Kung Fu had the villain laughing at your defeat—brilliantly rubbing salt in the wound! Now, this laughing motif pops up everywhere—films, TV, games—so common it’s often parodied.

Why Does Evil Laughter Stick Around?

The allure is simple. Evil laughter tells us a lot without words. It signals a character’s dark, often maniacal will. As Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen explains, evil laughter loudly broadcasts a villain’s pleasure in their wicked deeds, essentially calling out their moral corruption. It also invites us to despise them—and maybe even enjoy the scene a little.

Would a villain’s plan feel threatening without that chilling laugh? Probably not as much. It’s like the villain saying, “I know something you don’t, and I’m loving it.”

The Written “Mwahaha” vs. The Concept of Evil Laughter

It’s fun to remember that the text-based “mwahaha” variant is only a couple decades old, birthed around 2000 in early internet IRC chats and books. So if your intuition told you villains have been typing “mwahaha” since forever, no—this is a new kid on the block.

The sound of villainous laughter, on the other hand, has been echoing through human storytelling for over two millennia. It cropped up early in oral and written traditions, transitioning smoothly from epic poetry and tragedy to opera, theater, film, and digital media.

Think about how technology shapes storytelling—moving from word-of-mouth and theater to print, radio, film, comics, and video games. “Mwahaha” may just be the digital-age signature of something ancient but freshly typed.

So What’s the Takeaway?

- Ancient Greek tragedies give us the oldest recorded villainous laughter. It’s no innocent giggle but a sound rife with mockery and menace.

- The phrase “evil laughter” only got formal recognition in later centuries, but the feeling was always there.

- 19th-century opera and theater sharpened the trope with dramatic laughs tied directly to villainy.

- Early 20th-century films crystallized iconic villain laughs—think Wicked Witch and Evil Queen.

- Comics like Batman’s Joker popularized evil laughter in the visual and print realm.

- By 2000, “mwahaha” as a written tag was born out of online communities and early digital book printings.

- Video games adopted and parodied the trope, making villainous laughter a staple of modern entertainment.

Final Thoughts: Why We Love (and Laugh at) the “Mwahahaha”

Villainous laughter captures something universal—on the one hand, it reveals the villain’s evil joy. On the other, it’s just plain fun for the audience. It’s like a storyteller’s wink, a moment to enjoy the tension without taking it too seriously.

Next time you hear a mwahahaha, whether typed online or echoed in a movie theater, remember: You’re hearing an ancient tradition turned digital-age icon. It’s storytelling magic, coming full circle through time.

So, who do you think has the most memorable evil laugh of all time? The Wicked Witch? The Joker? Or perhaps that sneaky laugh from the villain in your favorite video game?