Monaco has a prince rather than a king mainly due to historical, political, and legal reasons tied to its status within European power structures and the Holy Roman Empire (HRE). Monaco’s rulers initially held the title “lord” and began styling themselves princes in the early 17th century. This change reflected both their actual political status and sensitivity to relations with more powerful neighbors. Declaring kingship would have implied equality with kings of much larger states such as France or Spain, a claim Monaco could not realistically assert.

In 1641, the Treaty of Peronne established Monaco as a French protectorate. This treaty confirmed the ruler’s right to their princely title but placed Monaco under French protection, reinforcing the delicate political balance. The title “prince” was thus appropriate and acceptable within the framework of Monaco’s limited sovereignty and its protectorate status.

The structure of the Holy Roman Empire also influenced Monaco’s titles. The Empire recognized few kings—primarily the emperor (King of the Romans) and the King of Bohemia. Monarchs within the empire were mainly dukes, princes, or electors. The empire regarded kingdoms as fully independent and self-governing entities, which Monaco was not. Although Monaco had largely become independent from the HRE by the 17th century, it remained legally part of it, restricting its rulers from assuming the title of king.

Comparisons with Austria and Prussia highlight this title diplomacy. Austria was an archduchy to signify prominence without claiming kingdom status within the HRE. Similarly, Prussia’s rulers initially adopted the title “king in Prussia” rather than “king of Prussia” to respect the HRE’s structure and other European powers. These titles served political strategies to avoid clashes over sovereignty claims.

Monaco, remaining a small territory with limited sovereignty and embedded in a complex geopolitical environment, adopted the title “prince” as a compromise reflecting its status. Kingship would have implied a level of sovereignty and power Monaco did not possess and would risk antagonizing dominant regional powers.

- Monaco’s early rulers were lords who became princes in the early 1600s.

- Monaco became a French protectorate in 1641, confirming princely titles.

- Calling themselves kings would equalize them with France/Spain, politically risky.

- The HRE recognized few kings; most rulers were princes or dukes.

- Austria and Prussia used lesser royal titles to maintain political balance.

- Monaco’s princely title fits its limited sovereignty and historical context.

Why does Monaco have a prince, rather than a king?

Monaco has a prince, not a king, because of its unique political history, the constraints imposed by neighboring powers, and the legal framework it existed within for centuries. Sounds like a simple title debate, right? But behind this lies a fascinating tale of medieval suzerainty, careful diplomacy, and political delicacy.

Let’s unpack the story, step by step, so you can impress your friends at your next trivia night or royal history discussion.

From Lords to Princes: Monaco’s Early Rule

Starting as a small territory under the suzerainty of Genoa, Monaco’s rulers were originally lords—in the late Middle Ages, no less. Back then, Monaco wasn’t a tiny luxury playground for yachts but a strategic enclave wrapped in the complex puzzle of Italian and Holy Roman Empire politics. Elders would tell tales of lords who ruled like mini-bosses, unable to claim grander titles because their land was a vassal state.

By the early 1600s, the rulers began to style themselves as princes. Now, why princes, not kings? Well, being a king implies power and sovereignty on a large scale, and Monaco was just too tiny and politically delicate for that. The title “prince” acknowledged authority but kept things modest enough to avoid stepping on any diplomatic toes.

The Treaty of Peronne: Monaco’s French Connection

The Treaty of Peronne in 1641 sealed Monaco’s fate as a French protectorate. Spain and France negotiated careful terms that allowed Monaco’s ruler to retain his rights and titles. This was a classic case of “You keep your crown, but you play by our rules.”

Because Monaco was under French “protection,” it made no sense to claim kingship. With France and Spain both watching closely, establishing oneself as a king next door would resemble showing up at their backyard BBQ and demanding the biggest piece of steak.

Political Sensitivities Around Being a King

Declaring kingship is more than a fancy title game. It meant asserting equality with other kings, notably the kings of France and Spain. Imagine suddenly announcing you’re “King of the Yachters” while your neighbors are rulers of massive kingdoms. It would ruffle feathers and likely invite conflict.

Thus, Monaco’s rulers wisely avoided antagonizing their powerful neighbors. Staying a prince was the savvy way to enjoy status without triggering diplomatic drama.

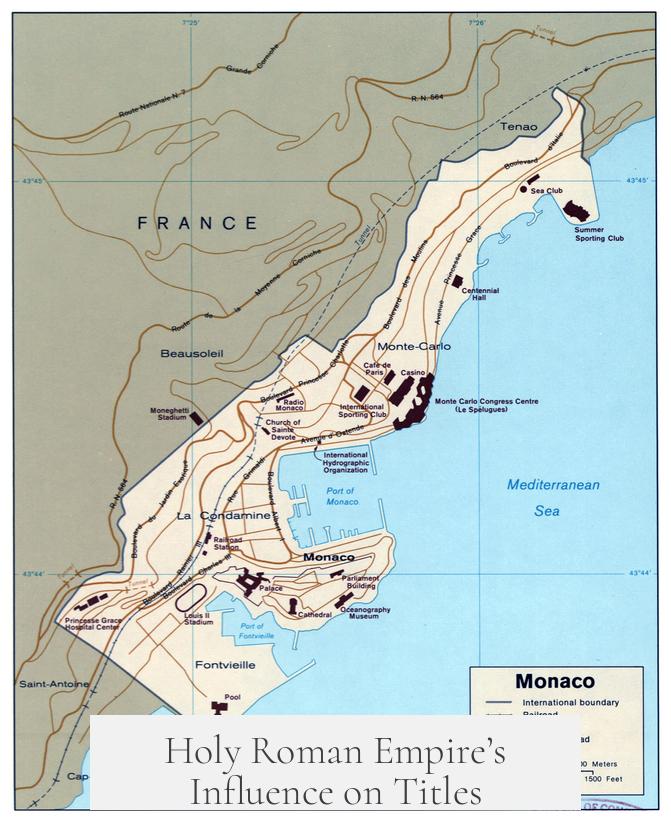

Holy Roman Empire’s Influence on Titles

Monaco was never part of the peerage of kingdoms in the Holy Roman Empire (HRE), which didn’t actually recognize many kingdoms within it—Bohemia being a prized exception. The HRE reserved kingship mostly for standout sovereigns like the “King of the Romans” (the emperor himself) and the “King of Bohemia.”

This empire’s rule was strict about who could claim what. Monarchs within the empire had to fit their ruler styles into a clear hierarchy to avoid chaos. Kingship signaled a degree of autonomy and considerable power, which Monaco simply didn’t match.

Archduchy vs. Kingdom: Austria’s HRE Balance

To draw a useful parallel, Austria was an archduchy, not a kingdom, within the HRE. This was meant to emphasize Austria’s higher rank among duchies without claiming full kingdom status. The Habsburg emperors, while powerful, ruled the empire, not Austria itself as a kingdom.

Only after the empire dissolved in the early 19th century did Austria become an empire outright. Monaco’s situation was different but shared the core principle: hierarchical titles matter, especially in a layered imperial system.

Prussia’s Subtle Title Game

Prussia’s rulers, like Monaco’s princes, had to carefully navigate the politics of their time. Brandenburg and Prussia were under a personal union but had different statuses under the empire. When the ruler wanted kingly status, he adopted the title “King in Prussia,” emphasizing that the kingdom was outside the HRE’s jurisdiction.

This subtle language was crucial—it acknowledged Prussia’s special status without provoking the HRE’s formal kingly hierarchy. Only much later did Prussia claim full kingship without qualifiers, reflecting geopolitical changes.

So, What Does This Mean for Monaco Today?

Monaco is still ruled by a prince, currently Prince Albert II of Monaco. The principality remains a sovereign state with its own government and laws but continues to embrace the legacy and title from its history.

Adopting “king” would clash with centuries of tradition, political realities, and the delicate balance Monaco has maintained in Europe. And let’s be honest, “Prince of Monaco” sounds pretty elegant.

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding why Monaco has a prince instead of a king shines light on how statehood and sovereignty can be a complex dance, not just a matter of land size or wealth. It reveals how historical treaties, imperial structures, and political games shape the titles leaders adopt.

Plus, it reminds us that in history, titles carry weight far beyond mere pomp—they reflect real power dynamics, diplomatic strategies, and the ambitions of nations big and small.

Summary for the Title Curious

- Monaco began as a lordship under Genoa in the late Middle Ages.

- Rulers started calling themselves princes in the early 1600s, not kings, to reflect status without threatening powerful neighbors.

- The 1641 Treaty of Peronne made Monaco a French protectorate, preserving princely titles but forbidding grander royal claims.

- The Holy Roman Empire’s hierarchy limited the use of kingship within its domain; Monaco was legally still part of it for a time.

- Examples from Austria and Prussia show how titles were carefully managed in the HRE to balance power and status.

- Monaco’s continued use of “prince” symbolizes political prudence and historical realities.

If history has taught us anything, it’s that sometimes smaller titles can come with bigger wisdom—and Monaco’s prince has been playing the royal game just right for centuries.

So next time you see a Monaco prince, you’ll know he’s not *just* a fancy figurehead—his princely title carries a centuries-old tale of diplomacy, survival, and just the right touch of regal humility.

Why is the ruler of Monaco called a prince and not a king?

Monaco’s ruler is called a prince because declaring kingship implied equality with powerful monarchs like the kings of France or Spain, which Monaco avoided to maintain political peace.

How did historical treaties affect Monaco’s princely title?

The 1641 Treaty of Peronne made Monaco a French protectorate but kept the ruler’s rights and titles as prince, not king, reflecting the delicate balance of power with France and Spain.

Did Monaco’s relationship to the Holy Roman Empire influence its ruler’s title?

Yes. Although Monaco was part of the Holy Roman Empire for a time, the empire recognized only a few kingdoms, and Monaco’s status and autonomy weren’t enough to claim a king’s title.

What does Monaco’s princely status have in common with Austria’s former titles?

Like Monaco, Austria avoided the king title within the Holy Roman Empire, using titles like archduke to show rank without claiming full kingship, reflecting limited sovereignty within the empire.

Why didn’t Monaco’s rulers claim to be kings despite ruling a territory?

Claiming kingship required independence and the risk of offending neighboring kingdoms. Monaco’s small size and political ties made the princely title a safer and more accepted choice.