The ancient Greeks lived in patriarchal societies, yet their mythology features powerful, strong-willed goddesses and women because these divine figures transcend human social rules, reflect men’s complex imagination of women’s inner lives, and symbolize real women’s varied and significant roles in Greek life.

The key reason is that gods and goddesses operate outside human norms. Mythological female deities like Athena, Artemis, and Demeter do not face the societal limits imposed on mortal women. They embody ideals and powers beyond human constraints, illustrating that divine narratives are not straightforward mirrors of social reality.

Ancient Greek men, despite living in patriarchal cultures, were surrounded by women daily—mothers, wives, lovers, and teachers. This intimate contact granted them empathy and insight into women’s experiences. Male authors could therefore craft rich female characters with depth and strength, even if official ideology promoted female seclusion.

The ideal woman in elite Greek literature was one who lived quiet, domestic lives. Yet economic and social circumstances meant that many women worked and appeared publicly. The ideal often clashed with reality; most city-dwellers needed women to manage household tasks and participate in public events, including religious festivals and ceremonies. Even wealthy women attended social functions, showing women’s active presence outside the home.

Women took on various public roles beyond domestic spheres. Some became poets, priestesses, philosophers, and princesses, acquiring public fame and influence. Greek men encountered women who were opinionated and commanding, demanding recognition as complete humans. This variety defies the notion of women as invisible or wholly submissive in Greek society.

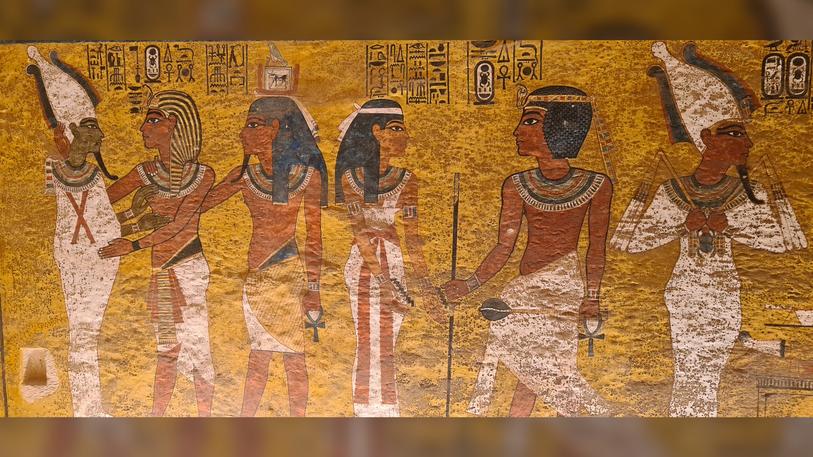

Cross-cultural interactions also shaped Greek perceptions of female power. Greeks met powerful women from other cultures like Persian queens or tyrants’ relatives. These encounters highlighted the existence of influential women who shaped political and social life. Such examples could have inspired the portrayal of strong goddesses and women in Greek myths, encouraging acknowledgment of female authority.

Modern scholarship challenges simplistic views of Greek women’s status as powerless or politically nonexistent. Women were recognized as citizens by birth in many poleis, could own and manage property, and sometimes even inherit land—especially in Sparta. Legal and social roles varied between city-states, with some affording women more agency than traditionally assumed. This complexity enhances understanding of women’s real participation in society.

Overall, Greek society’s patriarchy coexisted with significant female presence and power. Myths featuring strong goddesses do not contradict social patriarchy; instead, they reflect broader cultural dynamics. These myths reveal how men negotiated the reality of women’s influential roles through stories. Women’s power appeared both in divine fantasies and in concrete historical roles.

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Divine Transcendence | Gods and goddesses symbolize power beyond social norms. |

| Male Empathy | Greek men’s close relationships inspired nuanced female characters. |

| Social Reality vs. Ideal | Women lived public lives despite literary ideals of seclusion. |

| Women’s Public Roles | Women were poets, priestesses, philosophers, and more. |

| Cross-Cultural Contact | Exposure to powerful foreign women influenced Greek myths. |

| Legal Status | Women had citizenship rights and property ownership in some city-states. |

- Goddesses’ power transcends human societal limits.

- Greek men’s experiences with women fostered complex female portrayals.

- Economic and social conditions forced women’s active public participation.

- Women held varied and visible social, religious, and intellectual roles.

- Cross-cultural exposure encouraged recognition of female authority.

- Legal evidence shows women’s citizenship and property rights existed.

- Patriarchy coexisted with real female power and mythological celebration.

The Ancient Greeks Were Infamously Patriarchal and Often Misogynistic. So How Come Their Mythology Is So Filled with Powerful, Strong-Willed Goddesses and Women?

You might wonder: if ancient Greek society was deeply patriarchal, obeying strict gender norms that often sidelined women, why does their mythology shine with powerful goddesses like Athena, Artemis, and Demeter? How do fierce female figures thrive in a misogynistic world? The answer lies in the unique intersection of divine imagination, social realities, empathy, and cultural influences.

Let’s unpack this paradox with precision and a dash of curiosity.

Gods Aren’t Ordinary People: Mythology Beyond Human Rules

First, it’s essential to recognize that the gods of Greek myths aren’t human—they function outside human laws and social hierarchies. Men ruled, women were often relegated to secondary roles in daily life, but goddesses? They soared beyond earthly constraints.

The power of Athena, born fully armored from Zeus’s head, Artemis the huntress, and Demeter the earth mother, isn’t a contradiction of patriarchal society. It’s a signal that gods transcend human norms. Myths allowed storytellers to invent female figures with autonomy, authority, and influence no mortal woman would realistically wield.

This divine exemption made strong female figures acceptable in stories—even glorious—without threatening male dominance in reality.

Men Imagined Women’s Inner Lives—With Some Empathy

Still, mythology isn’t created in a vacuum. Ancient Greek men lived alongside women—mothers, wives, teachers, lovers. These men, often the very authors who penned myths and dramas, encountered women closely and respectfully. This intimate contact inspired complex female characters who voiced desires, fears, and opinions.

Imagine the playwright listening to his mother’s wisdom or watching his wife’s cleverness. That contact sparked empathy and nuanced imagination.

Greek male authors did not deny women’s humanity outright. They understood complexities, even if their cultural lens imposed limitations. That empathy gave birth to strong, vocal female characters in myth and literature—even as women’s own voices were muted elsewhere.

The Ideal Versus Reality: Women’s Roles Were More Fluid Than You Think

Books sometimes claim Greek women were locked away in seclusion, but real life laughed at these strict ideals. Economic necessity meant many women worked publicly, mingled socially, and were indispensable in family economies—not just shadows in the house.

Even aristocratic women had to step outside for weddings, funerals, and religious festivals. The ideal of the quiet, secluded woman fit the desires of elite men but wasn’t the universal truth. Greek society’s practical needs made women’s presence in public unavoidable.

So while societal narratives pushed a narrow role for women, the reality was more varied—giving scope for tales featuring women who moved, acted, and influenced beyond the home.

The Many Public Faces of Greek Women

Women appeared as poets, priestesses, philosophers, royal figures, and even prostitutes—the latter wielding influence in their own right. Greek history records women who took bold public roles and shaped events.

No man in ancient Greece was so isolated from reality that he never encountered women as full, active participants of public life.

These interactions surely inspired myths portraying convincing women whose stories stretched beyond domestic boundaries.

Influences from Other Cultures: Powerful Women Abroad Left Impressions

Greeks did not live in an isolated bubble. They encountered powerful women in neighboring empires, such as the Persian court, where women related to kings and tyrants exercised real power. These powerful foreign women were tangible reminders to the Greeks of women’s potential roles beyond Greek patriarchy.

Often, contact with other cultures opens eyes and stories. This contact likely enriched Greek mythology’s images of commanding goddesses and queens.

Modern Scholarship: Rethinking Women’s Status and Rights

It’s commonly said Greek women weren’t citizens, had no legal rights, and remained invisible. Modern historians challenge these claims.

Women were technically citizens by birth. Certain laws recognized them specifically. For example, property ownership and management were possible, especially in city-states like Sparta where women inherited land and wealth.

This varying legal status suggests women had agency—sometimes constrained, but not absent. The idea that they had no rights at all is too simplistic and rooted in narrow old definitions.

The Big Picture: A Society of Contrasts and Complexity

In the end, ancient Greek society was undeniably patriarchal, yet women were an undeniable, influential part of the world—visible in daily life, myth, and history.

The myths are a fascinating mirror. They reflect male recognition of women’s actual presence and power, though often filtered through patriarchal lenses. Mythology also serves as a bargaining space where male authors explored, expressed, and contained female strength through goddesses and heroines.

What Does This Teach Us?

- Powerful goddesses highlight the difference between mortal society and divine imagination.

- Empathy between sexes allowed Greek men to craft stories with real emotional depth for female characters.

- The social reality was more flexible—a million women weren’t all kept silent or secluded.

- Women’s public roles stretch across social, religious, and legal spheres.

- Cross-cultural exposure expanded Greek perspectives on female authority.

- Modern scholarship urges a nuanced understanding of women’s complex status.

This intricate web explains how a patriarchal society also gave birth to mythology rich with strong, complex women. Like Athena herself, wielding wisdom and war, these stories defy simple stereotypes.

Reflection: How Do We See Women Today?

Does this ancient tension between societal norms and female power sound familiar? It prompts a question: how often do modern stories reflect the complexities of women’s real lives rather than idealized or restricted roles? Greek mythology offers a reminder that female power expressed in stories doesn’t just emerge from acceptance—it may also emerge from resistance, imagination, and necessity.

So next time you read about the fierce Artemis or the cunning Medea, appreciate that their stories come from a world wrestling with women’s place: a patriarchal reality and a mythological dream.