The consensus on pederasty in Ancient Greece reflects complex social norms. It was broadly accepted when framed as a mentorship, involving an older man guiding an adolescent boy (around 14-16 years old) through education, manhood, and military training. This relationship publicly appeared as mentorship but included a sexual element known and tacitly accepted by society.

Many Greeks valued a strong power imbalance in relationships. Unlike modern views that criticize unequal power dynamics, Ancient Greek culture idealized adult men as active and dominant partners. The older man often offered gifts to gain the boy’s favor and was considered a mentor if the boy was aristocratic. However, pederasty also involved slaves, indicating it cut across social classes.

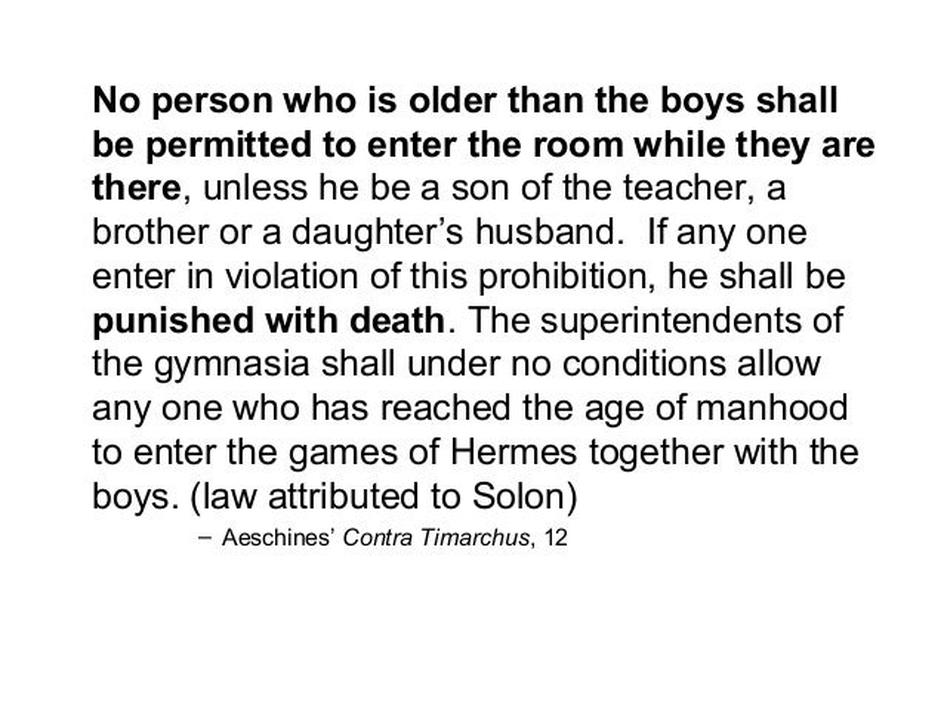

Criticism existed despite this acceptance. Some ancient Greek plays contained sarcastic lines mocking aristocrats for engaging in such relationships. These remarks suggest public awareness coupled with subtle disapproval. Importantly, penetrative sex between men and boys was generally prohibited. Artistic depictions show alternative sexual acts intended to avoid “emasculating” the boy, such as penetrating the boy’s thighs pressed together. Deviations from these norms caused social trouble, including family disapproval.

Philosophers and historians also debated these practices. Paul Veyne, a modern historian, notes that platonic love was tolerated more than explicit sexual relations. This viewpoint matches some ancient criticisms that celebrated the emotional and educational facets rather than the sexual ones.

A Greek writer from around 180 AD criticized non-Greek peoples trying to imitate Greek customs of boy lovers but corrupting them, highlighting a cultural boundary between Greeks and “barbarians.” Plato’s stance is sometimes debated. While some interpretations claim he opposed homosexuality and pederasty, others argue his views were nuanced, emphasizing moral and philosophical concerns over outright approval or rejection.

- Pederasty was socially accepted as a mentorship with expected mentorship duties.

- Power imbalance and active male roles were idealized.

- Penetrative sex was disapproved; alternative sexual acts were preferred.

- Public criticism existed through satire and social scrutiny.

- Platonic love was more accepted than sexual involvement.

- Cultural distinctions marked Greek acceptance versus foreign imitation.

- Philosophers like Plato expressed varied opinions emphasizing ethics.

What’s the Consensus on Pederasty in Ancient Greece?

In Ancient Greece, pederasty was broadly accepted but with tightly defined social rules and significant scrutiny. The practice, involving an older man and a teenage boy, blended mentorship with romance and sex, but society demanded it look more like education and guidance than mere pleasure. Sounds like an awkward mix? It was—and the Greeks knew it.

Let’s dive deep into the ancient world where power, mentorship, affection, and social status collided in tangled formations. What was normal then might raise eyebrows today, but understanding the consensus uncovers layers of cultural complexity.

The Mentor-Student Facade: More Than Meets The Eye

Ancient texts, especially those by Xenophon, describe pederasty under a veil—it was acceptable, but only if it dressed itself as a mentorship between an older man and a boy around 14-16 years old. The mentor gave gifts, taught practical skills, especially arms training, and supposedly led the boy toward adulthood. That’s the textbook version.

But anyone reading between the lines knew the physical and emotional connection extended beyond formal coaching sessions. So, while mentorship formed the “official” framework, the real picture was a consensual, if socially bounded, relationship where attraction and power played key roles.

Power Imbalance: Ideal or Problematic?

Today, we cringe at huge power differences in relationships. But in Ancient Greece, these imbalances were the ideal—adult men were expected to be dominant in romance and sex. Boys played the passive role, which aligned with society’s strict ideas about masculinity and social hierarchy.

Power, in this context, was part of teaching and socializing. The older man didn’t just instruct about fighting or politics; he shaped the boy’s character and identity. Aristocratic boys especially were under such tutelage, though this dynamic sometimes extended to slaves too.

Social Scrutiny and Limits: The Boundaries of Acceptability

Not everyone was cheering on this practice. The Greek stage offers clues—comedies and plays contain snarky remarks about wealthy aristocrats bedding boys. These jokes suggest ambivalence. Everyone knew pederasty happened, but it was also ripe for criticism and ridiculement.

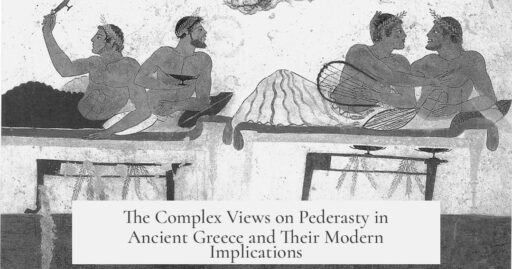

And here’s a critical boundary: penetrative sex between the man and boy was taboo. Greek pottery sometimes depicts a workaround called “intercrural” sex—where the man penetrates between the boy’s pressed thighs, avoiding actual anal intercourse. The idea? Preserve the boy’s masculinity by preventing what was seen as emasculating acts.

Not following these social rules could lead to scandals and family conflicts. The boy’s family might object, and playwrights caught these transgressions, peppering their works with veiled critiques.

Platonic vs. Sexual Love: A Dividing Line

French historian Paul Veyne notes that purely platonic love between man and boy was tolerated—maybe even admired as a form of deep affection or soul-connection. But actual sexual relationships got a lot of flak. Sex was the controversial twist that complicated otherwise respected mentorships.

Some ancient voices even compared Greek pederasty to “barbarian” imitations. Around 180 AD, a Greek author described how settlers in Crimea tried to preserve classical customs, including these boy lovers. Yet, he harshly criticized non-Greeks who copied this practice badly, making it “disgusting” by violating Greek customs. Seems even back then, cultural authenticity mattered.

What Did Plato Think?

Here’s a twist: Plato, often linked with discussions on love and philosophy, was reportedly skeptical or even disapproving of pederasty. The philosopher emphasized the soul and higher forms of love rather than physical or erotic connections. His dialogues sometimes elevate “platonic” love and warn against base desires.

So the idea that ancient Greece unanimously celebrated pederasty is a myth. Plato’s reflections suggest that even within the culture, opinions varied, and some considered sexual acts between men and boys problematic rather than ideal.

What Can Modern Readers Learn?

Understanding ancient pederasty requires unpacking a dense stew of social expectations, power dynamics, cultural norms, and philosophical debates. It wasn’t simply “old-school grooming” or a predatory practice—it was a recognized social institution, albeit one enmeshed with conditions and critiques.

For anyone exploring ancient ethics, the tensions tell us how deeply culture shapes sexual morality. The Greeks wanted the ideal balance of mentorship and affection, wrapped in well-understood social limits. Crossing these lines sparked gossip and satire, even as the practice endured.

See how history’s hard rules differ from ours? It puts awkward questions on the table: How do power and consent mix? Can mentorship truly be separated from attraction? And what does it mean to “teach a boy to be a man” when masculinity itself is socially constructed?

In Conclusion

The consensus in Ancient Greece accepts pederasty but only within tight social and cultural boundaries emphasizing mentorship, power imbalance, and non-penetrative sex. Anyone stepping outside these bounds risked social censure, satire, or worse.

While the topic challenges modern sensibilities, approaching it with historical perspective shows us a society grappling with complex relationships and moral codes. These ancient customs reflect specific views on power, sex, love, and education—not timeless standards.

Isn’t history fascinating when it forces us to rethink what we consider “normal”? Now you know—the Greeks played a delicate balancing act with pederasty that mixed caring guidance with social control. Next time you read a comedy about “rich men and boys,” you’ll see it’s not just humor but a window into ancient cultural struggles.