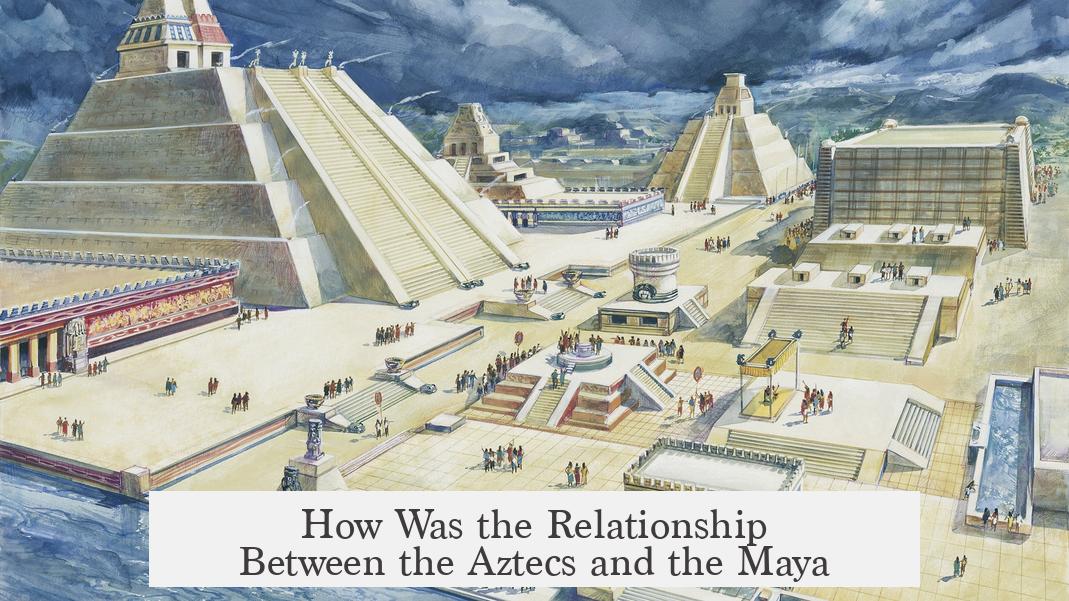

The relationship between the Aztecs and the Maya was limited and largely indirect, shaped by differences in time periods, territorial reach, and cultural contexts. The Maya civilization spans from before 500 B.C. to the present, while the Aztec empire existed briefly between 1428 and 1521 A.D. Because of this disparity, their direct contacts cover only a small slice of Maya history. Most interactions took place in a narrow window during the late Postclassic period.

Territorially, the Aztecs conquered only one Mayan-influenced region: Soconusco. This coastal area near the modern Mexican-Guatemalan border represented a cultural corridor mixing Mixe-Zoquean and Mayan peoples. The Aztec emperor claimed it around 1486, primarily to control its cacao production and collect tribute from at least eight local towns. Soconusco likely played a minor role within the Aztec empire beyond providing tribute goods such as cacao.

Beyond Soconusco, direct contact was scarce. The Aztecs and Maya knew of each other through longstanding Mesoamerican trade networks. These routes spanned vast distances, connecting diverse cultures. Traders and intermediaries relayed goods across regions, meaning Mayan and Aztec peoples exchanged items without necessarily meeting directly. This trade system allowed exchange of commodities and potentially some cultural elements without significant face-to-face interaction.

Despite limited direct contact, the Aztecs and Maya shared cultural features due to millennia of regional interaction. For example, both peoples worshipped a feathered serpent deity: Kukulkan to the Yucatec Maya and Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs. This religious symbol shows a deep history of diffusion, not a direct connection stemming from Aztec-Maya encounters. Such motifs reflect centuries of cultural exchange that predate the Aztec empire.

A unique case involves the Huastecs, a Maya-speaking people located far north of the main Maya region, in northeastern Mexico. The Aztecs conquered several Huastec towns during Motecuhzoma I’s reign around 1450. The Aztecs saw the Huastecs as socially and culturally inferior, often depicting them as “filthy” and uncivilized. This portrayal served to morally contrast Aztec virtues against their subjects and to position the Huastecs as providers of chaotic, powerful energy within Aztec ideology.

The Huastecs’ subordination illustrates a colonial dynamic where the Aztecs absorbed a distinct Maya group into their empire. Despite cultural denigration, elements of Huastec symbolism were integrated into Aztec religious practices. This reflects a complex relationship mixing domination, symbolic appropriation, and marginal cultural exchange.

It is important to recognize that much of the historical record on Aztec-Maya relations, especially regarding the Huastecs, comes from Nahuatl sources filtered through Aztec perspectives. These sources tend to emphasize Aztec viewpoints and often cast subjugated peoples in negative terms. Consequently, the Maya perspectives—both in Soconusco and among the Huastecs—remain difficult to reconstruct fully. Contemporary Maya groups in northern Veracruz and San Luis Potosí continue to speak Mayan languages, but ethnographic knowledge about these communities’ views on Aztec conquest is limited.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Timeframe | Maya civilization: >2000 years; Aztecs: 1428-1521 |

| Territorial Conquest | Aztecs conquered Soconusco, a mixed region, for cacao tribute |

| Direct Contact | Minimal beyond Soconusco; mostly indirect via trade networks |

| Cultural Similarities | Shared motifs like feathered serpent due to long-term diffusion |

| Huastecs | Maya-speaking group in northeastern Mexico, conquered and subordinated |

| Sources | Nahuatl-centric, limit understanding of Maya perspectives |

The mosaic of Aztec-Maya interactions shows a relationship marked by temporal distance, limited military expansion, and indirect economic ties. Conquest was selective and modest, focused on specific resource-rich localities rather than broad Maya control. The Aztecs and Maya maintained awareness of each other mainly through trade routes established long before the Aztecs’ rise. Over time, cultural diffusion linked these civilizations in shared symbols and ideas.

The Huastec case is exceptional, revealing how Aztec colonial power assimilated a Maya subgroup far outside the southern lowlands. The Aztec narrative framed this conquest through a lens of cultural moral judgment and exoticism. Gaps in historical records and ethnographic data hinder full comprehension of Maya self-perceptions and the nuances of their relations with the Aztecs.

- The Aztec-Maya relationship was minimal with brief periods of direct interaction.

- Aztec conquests in Maya spatial domains were limited to Soconusco and Huastec towns.

- Trade networks facilitated indirect contact and exchange of goods.

- Shared cultural elements emerged from long-term regional diffusion, not direct ties.

- Huastecs experienced Aztec colonial subjugation, reflecting complex cultural dynamics.

- Historical understanding relies predominantly on Aztec sources, limiting Maya perspectives.

How Was the Relationship Between the Aztecs and the Maya?

The relationship between the Aztecs and the Maya was minimal, mostly indirect, and limited to just a small period in history. The two civilizations flourished at different times and places, resulting in barely overlapping interactions.

Imagine two powerful neighbors who live decades apart and have only one narrow street connecting their homes. That’s basically how the Aztecs and Maya connected. The Maya have a history spanning over two millennia, from before 500 B.C. and continuing into today. The Aztec empire, meanwhile, was a flash in the pan—existing mainly from 1428 to 1521. So, when we chat about their relationship, we’re really zooming in on just a tiny slice of Mayan history during the Aztec late appearance.

One Conquest, One Flavor: Soconusco

The Aztecs’ only real territorial grab in a culturally Mayan area was the Soconusco region. Located near today’s border of Mexico and Guatemala, on the Pacific coast, Soconusco wasn’t fully Mayan. It was a mixed cultural corridor between the Mixe-Zoquean speakers and the Maya.

In 1486, the Aztec emperor conquered Soconusco and started collecting tribute, especially cacao, from at least eight towns. Cacao was a big deal then—think of it as the luxury chocolate currency of the Mesoamerican world. Despite this, Soconusco had little importance within the Aztec empire besides paying tribute. Its cultural mix highlights how boundaries between peoples in Mesoamerica were blurred and fluid.

Trade, Not Friendship: Indirect Contact Reigns

Beyond Soconusco, direct contact between Aztecs and Maya was minimal. They knew of each other, sure, but real interaction was mostly through long trade networks and intermediaries. Traders moved goods across the region, linking Central Mexico and the Maya territories indirectly. It’s even possible that Aztecs and Maya traded items without meeting face to face.

This kind of “magical mystery trade tour” meant that goods and ideas circulated widely, but the people behind them often remained strangers with just a nodding acquaintance.

Shared Gods, Shared Culture? Not Exactly.

Despite their differences and scant direct contact, both civilizations shared some cultural elements. The famed feathered serpent deity—called Kukulkan by the Yucatec Maya and Quetzalcoatl by the Aztecs—is one such example.

However, these shared religious symbols aren’t proof of close ties between them during the Aztec Empire’s reign. Instead, these similarities come from millennia of constant interaction and cultural diffusion across Mesoamerica. In other words, culture seeped through the region like a slow-moving river, rather than a sudden handshake between neighbors.

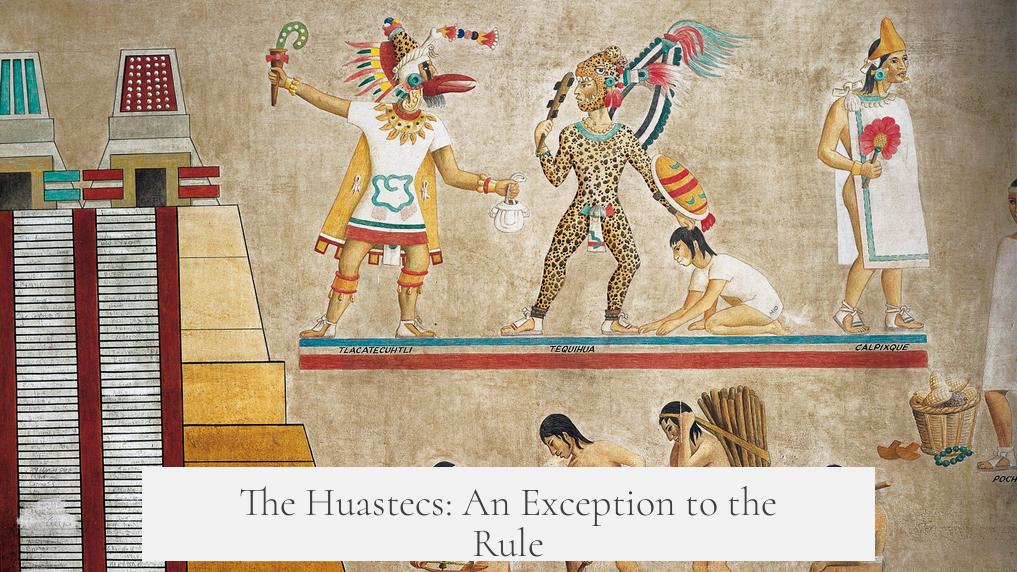

The Huastecs: An Exception to the Rule

Let’s detour a bit to the Huastecs, a Maya-speaking group living far north of the main Maya areas, around northeastern Mexico. The Aztecs conquered several Huastec towns around 1450 during Motecuhzoma I’s rule. However, the Aztecs viewed the Huastecs as “filthy” and barely civilized—classic colonial attitude of the conqueror.

Despite this disdain, the Huastecs held a unique place in Aztec culture and symbolism. They represented a wild, chaotic power that the Aztecs found rhetorically useful. The relationship was one-sided colonial subordination rather than friendship or alliance.

Reading Between the Lines: Source Bias Matters

When we try to understand the Aztec-Maya interaction, we rely heavily on records written or interpreted by the Aztecs themselves or their Nahuatl-speaking descendants. This introduces bias, especially regarding groups like the Huastecs. What did the Huastecs think of the Aztecs? That remains a mystery.

Modern Huastec speakers still live in northern Veracruz and San Luis Potosí, but their historical views on the Aztecs are seldom recorded. So, caution is warranted when interpreting their story through the lens of Aztec victors.

Summary: A Brief and Mostly Indirect Encounter

- The Aztec empire existed for less than 100 years, while the Maya civilization spanned thousands, limiting their overlap.

- The Aztecs conquered only one culturally mixed region with Mayan influence, Soconusco, largely for tribute like cacao.

- Outside of conquest, contact was mainly indirect through trade networks, with little direct interaction.

- Mesoamerican cultural similarities, such as shared deities, evolved over millennia and don’t indicate close Aztec-Maya ties.

- The Huastecs, Maya speakers in northern Mexico, were colonized and looked down upon by the Aztecs but symbolically important.

- Historical accounts are mostly Aztec-centered, complicating the full picture of relationships.

What Can We Take Away?

The Aztec-Maya relationship defies a neat story of neighbors sharing friendly banquets or fierce battles. Instead, it’s a patchwork of limited conquests, indirect trade connections, and shared cultural elements shaped over centuries. It reminds us that ancient civilizations often interacted in complex, multi-layered ways—not always face to face.

So next time you munch on chocolate or admire a feathered serpent motif, you’re connecting to a centuries-old dance of cultures that blended and borrowed across the Mesoamerican landscape—not just Aztec or Maya alone but a shared heritage shaped by many.