People did not believe that a dingo ate the baby largely due to a mix of cultural beliefs, investigative bias, conflicting evidence, and media influence. Doubts stemmed from initial skepticism about dingoes attacking humans and suspicions focused strongly on the parents, especially Lindy Chamberlain. The unique context and contradictory official findings fueled public disbelief for decades.

At the heart of disbelief was the prevailing assumption that dingoes did not pose a threat to humans. In two centuries of recorded European settlement in Australia’s Northern Territory, no confirmed fatal dingo attacks on humans had occurred before Azaria Chamberlain’s disappearance. Local skepticism was reinforced by police attitudes and community beliefs. When Azaria vanished from the family campsite near Uluru in 1980, the idea that a dingo could have taken a baby seemed implausible to many. This belief was underpinned by eyewitness accounts and expert opinions from local grazier communities, which held that dingo attacks on humans were “a million to one chance.”

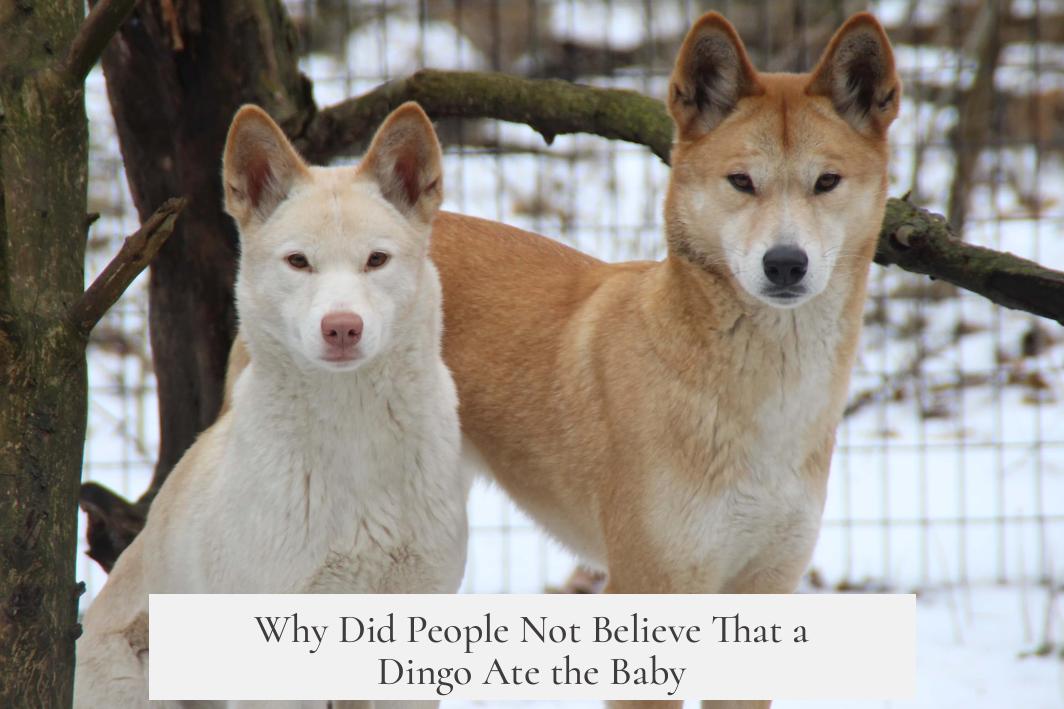

Contrasting this was the Indigenous oral tradition around Uluru, which included accounts of dingo attacks, even on children. Indigenous trackers at the camp site supported Lindy and Michael Chamberlain’s version of a dingo attack. However, cultural and linguistic barriers prevented these testimonies from gaining full legal respect. The court system never heard Aboriginal evidence in situ, and the misunderstanding of Aboriginal ethics and knowledge led to valuable expert insights being excluded from trials. This contributed to the public and official dismissal of the dingo theory.

Investigative bias significantly colored the course of the case. The police and media focused heavily on the Chamberlains’ behavior. Reports circulated that Lindy appeared indifferent to Azaria, dressing the baby in black and lacking typical maternal responses. Such characterizations amplified public suspicion. Police officers expressed prejudiced views, including bizarre comments about the family’s appearance and demeanor. This personal and irrational bias influenced how physical evidence was treated.

Physical evidence suggestive of a dingo attack, such as paw prints near the tent, canine hairs, and teeth marks on the baby’s blanket, were dismissed or interpreted as staged. Senior investigators argued that the damage to the blanket looked like cuts from a sharp instrument, not dog bites. This flawed reasoning was part of a larger pattern of “junk science” offered by competing experts during the trials. It reinforced the narrative that the Chamberlains fabricated the dingo story to cover a murder or accidental death.

| Factor | Effect on Belief |

|---|---|

| Lack of prior fatal dingo attacks | Created general disbelief in dingo danger, especially toward babies |

| Indigenous oral histories ignored | Undermined credible local knowledge supporting dingo attacks |

| Investigator and police bias | Shifted suspicion unfairly onto Chamberlain family |

| Dismissal of physical evidence | Reinforced narrative of staged crime scene |

| Contradictory official inquests | Created confusion and fostered ongoing doubt |

| Media and public gossip | Amplified rumors and suspicion about parents |

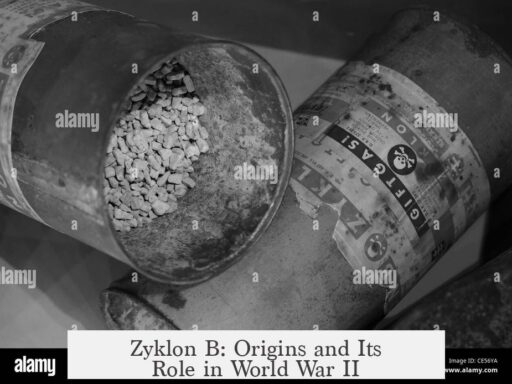

Initial legal processes deepened skepticism. The first inquest, held within months, suggested a dingo attack as likely but left key questions unresolved. It noted the baby’s body had been moved by unknown persons, implying complexity beyond a simple attack. The Northern Territory police rejected the findings and reopened investigations. Later, the Supreme Court quashed the first inquest’s verdict due to questionable forensic evidence, including supposed bloodstains later identified as a chemical compound commonly found in vehicles.

The second inquest took a formidable turn, charging Lindy Chamberlain with murder and Michael as an accessory. Both were found guilty in trials relying on forensic evidence that appeared convincing at the time but would later be discredited. The verdict shaped public opinion strongly against the dingo attack theory. While some Australians formed the Chamberlain Innocence Committee to challenge the verdicts, police and court rulings prevailed in public perception for years.

Media coverage was relentless and often sensational. It highlighted Lindy’s demeanor and questioned her accounts, often distorting facts. The narrative of a cold, possibly murderous mother captured public attention. Gossip and innuendo asserted that the Chamberlains crafted the story to conceal the baby’s death. Such coverage disregarded the traumatic loss and overlooked alternative truths.

Only decades later, with a fourth inquest in 2012, did official conclusions unanimously confirm that Azaria Chamberlain died from a dingo attack. This ruling clarified the facts, exonerating the Chamberlain family fully after years of false accusation. Despite this, longstanding disbelief lingers due to years of conflict, poor handling of evidence, and cultural misunderstandings.

- People doubted a dingo attack because they believed dingoes did not attack humans, especially babies.

- Indigenous oral histories substantiating dingo attacks were ignored due to cultural misunderstandings.

- Police and media biases targeted the Chamberlains, interpreting physical evidence as fabricated.

- Contradictory legal findings fueled uncertainty and ongoing speculation.

- Public opinion was shaped by rumors, suspicions, and sensational media reporting.

- Definitive confirmation only came with the 2012 inquest, long after the event.

Why Did People Not Believe That a Dingo Ate the Baby?

The simple answer is: people found the story too strange; conflicting evidence, cultural misunderstandings, police biases, and powerful media narratives created a perfect storm of skepticism about the dingo attack theory. Let’s unravel this knot together and explore why so many doubted that a wild dingo was the culprit behind the tragic disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain.

The Initial Waves of Doubt

Right after the incident, the official inquiry, held just four months later, suggested a dingo probably took Azaria. Sounds straightforward, right? But it wasn’t just a clean conclusion. Mr. Barritt, who led the inquest, highlighted a bizarre and unsettling detail: Azaria’s body had been moved away from where the dingo supposedly took her. That’s like discovering a puzzle piece missing and another person sneaked in to fiddle with the arrangement. Naturally, suspicion swirled.

Northern Territory (NT) police didn’t buy it outright either. They kept the investigation open, interviewing others and searching for more clues. For many, this hinted at loose ends and maybe a hidden truth lurking beneath the surface. It’s hard to rally behind a theory when the law enforcement itself appears uncertain.

Quashing the First Inquest and the Role of “Evidence”

Things took a dramatic turn when the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory quashed the first inquest’s findings. What disrupted this early conclusion? Bloodstains found in the car and new forensic evidence by Professor James Cameron, which made investigators question everything. In the public eye, such developments often sound the alarm—if there’s so much conflicting evidence, maybe the truth isn’t the simple wild animal attack story they initially told us.

The Second Inquest and Trial’s Shadow Over the Chamberlains

Next came the second inquest and the subsequent trial that changed everything. The state boldly charged Lindy Chamberlain with murder and Michael Chamberlain as an accessory after the fact. Lindy ended up jailed for life amid hard labour—a grueling punishment for a desperate family.

Many Australians believed in the Chamberlains’ innocence, forming the notable Chamberlain Innocence Committee. But the evidence during the trial seemed pretty solid at the time: bloodstains, forensic testimony, physical marks. What they didn’t realize then was that some of this evidence was faulty—like the “bloodstains” that were actually a chemical compound manufactured inside the car. Put simply, this wasn’t cheap soap opera drama; it felt legally convincing to many.

Why Were Dingoes Such Unlikely Suspects?

Here’s a nugget of knowledge you might not expect. Most Australians—and frankly, many authorities—didn’t think dingoes could attack humans, especially children. After all, in 200 years of recorded white settlement, fatal dingo attacks were nearly unheard of, with only one or two exceptions outside the Northern Territory. This factual backdrop meant when police first heard the news, they assumed a hoax. Imagine that: a wild dog attack seemed so improbable they treated it like a prank call.

Locals and graziers confirmed this idea, saying that attacks on humans were practically “a million to one chance.” That’s the kind of skepticism that shapes public opinion fast. If nature teaches you dingoes keep their distance, then the notion of a wild dingo snatching a baby sounds like science fiction.

The Overlooked Indigenous Oral History

The real twist? Indigenous communities around Uluru had long-standing oral histories detailing dingo attacks on humans, including infants. This evidence was solid, passed down over generations, but calls of cultural and language barriers meant white authorities often either misunderstood or ignored these insights.

Even though senior indigenous trackers and rangers like Derek Roff treated Lindy and Michael’s account with respect, the legal system failed to properly consider this crucial input. Charges of “ethnic confusion” and systemic bias paint a bleak picture of justice here. It’s a classic example of how different perspectives clash, with tragic consequences.

Suspicions about the Chamberlains: A Case of Character Assassination?

Now, throw in some juicy rumors and people naturally start doubting motives. The Chamberlains’ media interviews early on raised eyebrows. Reporters thought they seemed “too willing” to talk, which can feel suspicious in a tragedy. Lindy’s behavior was described as cold and uncaring—such as dressing baby Azaria entirely in black and seeming emotionally detached.

Medical staff and reporters whispered about her, even digging into the meaning of “Azaria,” which is said to mean “sacrifice in the wilderness.” Can you spell drama? This mix of personal judgment and superstition painted the Chamberlains in an unfortunate light, fueling public distrust long before any court verdicts.

Law Enforcement Biases and Flawed “Science”

Sadly, some police officers displayed glaring biases. One officer suggested Lindy’s son should be investigated because “he’s got very weird eyes.” Another claimed Lindy herself had “killer eyes.” These kinds of statements read like bad fiction, but they actually shaped the investigation.

Physical evidence that supported a dingo attack, like paw prints and canine hairs, was dismissed as a staged scene by the parents. The skepticism extended to what was called “junk science” — experiments designed to disprove dingo involvement rather than neutrally investigate. For example, a police report said the baby’s blanket had cuts “more like a knife than dog bites,” asserting that everyone knows what dog bites look like, conveniently ignoring the fact that wild dingo teeth are different from domestic dogs’.

The Media’s Role in Shaping Public Opinion

As the inquest judge Barritt noted, the Chamberlains suffered not only the grief of losing their daughter but a torrent of “innuendos, suspicion and probably the most malicious gossip issued in this country.” The media had a field day. Many Australians lumped together their disbelief about dingo attacks and the family’s ‘strange’ behavior to form a judgment hard to undo.

This gossip frenzy meant even when later inquests, including a fourth one in 2012, officially declared a dingo responsible for Azaria’s death, many minds were already made up. The damage was done—once a narrative sets in public opinion, especially with media backing, it’s tough to pull back.

Lessons and Reflections: What Made the Doubt Stick?

- **Historical Rarity:** Few recorded dingo attacks made the idea seem impossible; it conflicted with collective knowledge.

- **Cultural Disconnect:** Indigenous knowledge was overlooked, highlighting the gaps between oral history and official records.

- **Bias & Prejudice:** Police and media biases against the Chamberlains fueled alternative crime theories.

- **Faulty Forensics:** Misinterpretations and “junk science” evidence muddled the facts.

- **Conflicting Legal Outcomes:** Changing inquest decisions caused confusion and doubt.

- **Media Influence:** Sensationalism shaped public perception, often sidelining truth.

So, why did people not believe a dingo had taken the baby? Because the story was tangled in a web of social, cultural, legal, and scientific misunderstandings, peppered by prejudices and sensational media. It wasn’t just the crime scene that was complicated—the whole narrative surrounding Azaria’s disappearance became a murky tangle of truth and doubt.

Can This Story Teach Us Anything New?

Absolutely. It reminds us how important it is to question our assumptions. Just because something feels unlikely doesn’t make it impossible. Stories from Indigenous communities are valuable and deserve respectful attention. And perhaps, we should be wary of letting emotions and media hype drown out careful investigation.

Next time you hear an unbelievable story, ask yourself: Are we stuck in our biases? Could there be unseen truths beyond the surface? The Chamberlain case teaches that justice demands humility, open minds, and a fearless look at facts—no matter how uncomfortable they may seem.