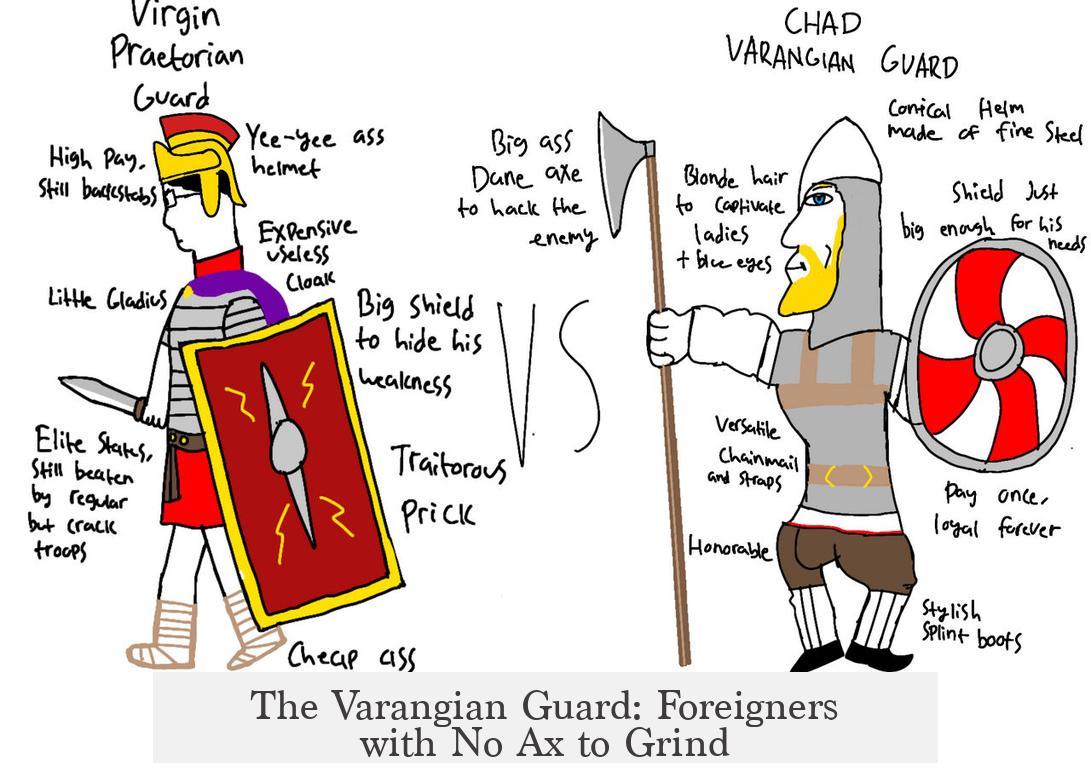

The Varangian Guard maintained loyalty to the Byzantine emperor because they were foreign mercenaries without local political ties, whereas the Praetorian Guard’s Roman citizenry and local entanglements enabled them to become kingmakers. This fundamental difference in composition and allegiance explains their divergent roles in imperial politics.

The Praetorian Guard originated as an elite unit assigned to protect senior Roman officials and, eventually, the emperor. Membership shifted from freedmen or slaves to decorated Roman legion veterans. This unit enjoyed unique privileges: exclusive armament rights within Rome and direct access to the emperor. These factors gave the praetorians unprecedented political influence.

Being Roman citizens deeply integrated into local society, the praetorians held social and political ties within Rome. Their proximity to the emperor and monopoly on armed presence in the capital turned them into key power brokers. They often intervened in imperial succession and politics, sometimes deposing and appointing emperors. This repeated interference earned them a notorious reputation as kingmakers.

The motivation for their political meddling stemmed partly from high pay and lavish privileges. Historical records show that praetorians received “pay-and-a-half,” substantially more than regular legionaries, incentivizing the guard to leverage their power for rewards. For example, under Emperor Domitian, their annual pay reached 1,500 denarii per soldier. Emperors often sought to secure praetorian loyalty by granting copious donatives and honors, which further encouraged political manipulation.

Over time, dissatisfaction with their conduct and ambitions led to their decline. By 284 AD, the praetorian guard fell out of imperial favor. Their traditional role guarding the emperor’s residence was revoked, and they were largely replaced by the Scholae Palatinae. The new unit drew heavily on foreign Germanic cavalrymen and did not match the praetorians’ predilection for political intrigue.

In contrast, the Varangian Guard was formed around 911 AD in Byzantium amid a need for a loyal elite force to protect the emperor from both external enemies and local political threats. The guard primarily comprised foreign mercenaries, often Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons, who lacked local political affiliations or ambitions within the Byzantine state.

This foreign status was a crucial asset. Detached from Byzantine noble factions and citizen networks, the Varangians had no personal stakes in internal court politics. Their loyalty was tied directly to the emperor as their employer, maintained through strict discipline and reliable pay. Unlike the praetorians, who could influence politics to their benefit, the Varangians had limited incentive to intervene.

Historical examples support this. The Varangian Guard served faithfully in combat and palace security for over 350 years without becoming political kingmakers. Their predecessors, such as the Batavian mercenaries in Roman service, shared this apolitical loyalty, serving out of duty rather than factional interest.

| Aspect | Praetorian Guard | Varangian Guard |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Roman citizens, decorated legionnaires | Foreign mercenaries (Norse, Anglo-Saxon) |

| Political ties | Strong local connections within Rome | No local political affiliations |

| Access to emperor | Unlimited, armed presence in capital | Close, but detached and professional |

| Motivation | High pay plus political gain | Strict pay-for-service loyalty |

| Role in politics | Kingmakers, political interference | Defenders, minimal political meddling |

The praetorians’ embeddedness in Roman society bred divided loyalties. Their role evolved beyond protection to actively shaping imperial politics, often through ruthless measures. Meanwhile, the Varangians’ foreign origins kept them as professional soldiers dedicated to military duties and palace protection. Their lack of factional loyalty curtailed ambitions beyond their official role.

In essence, the Varangian Guard’s loyalty stems from their outsider status and mercenary discipline, while the praetorian guard’s local integration provoked political ambitions and enabled them to become kingmakers.

- Praetorian Guard were Roman citizens deeply tied to local politics, enabling power plays within the empire.

- They held exclusive arms in Rome and access to the emperor, fueling political interference.

- High pay and political favors motivated praetorians to act as kingmakers.

- Varangian Guard were foreign mercenaries with no local ties, relying solely on loyalty to the emperor.

- The Varangians’ detachment minimized political ambitions, focusing their role on protection and military service.

Why Were the Varangian Guard Loyal While the Praetorians Turned into King Makers?

Let’s cut to the chase: the Varangian Guard remained loyal because they were foreign mercenaries with no local ties or political agendas, while the Praetorian Guard, composed of Roman citizens deeply connected to the capital’s politics, exploited their proximity and power to become king makers.

Now, grab your historian’s hat as we unravel why two elite guards, both charged with protecting emperors, had such divergent paths.

The Praetorian Guard: From Protectors to Power Brokers

The Praetorian Guard starts its story as a prestigious unit of the Roman army. They weren’t just any soldiers—they were handpicked veterans, seasoned and decorated, initially tasked with guarding senior Senate members, then the Emperor himself.

Think of them as the Emperor’s personal bodyguards with serious street cred. Their ranks, by design, included Roman citizens, veterans who had social and political stakes in the city. This wasn’t your average army: they were armed, allowed to carry weapons even inside Rome’s sacred city limits, and had unrestricted access to the Emperor. Talk about being gatekeepers! This setup turned out to be a double-edged sword.

Unlimited access plus political and military might created a perfect storm. The Praetorians quickly realized they had leverage—more than muscle, they had a say in who held power. For example, countless Roman emperors owed their thrones to Praetorian backing or, at minimum, their survival to the Guard’s favor.

The Guard’s political meddling became so notorious that they frequently orchestrated coups, assassinations, and kingmaking endeavors—sometimes for pay, sometimes for prestige. You might say they enjoyed perks that would make a modern-day lobbyist jealous: “pay-and-a-half” (150% the pay of a regular legionary!), lavish donativa (bonuses), and hefty honors.

During Emperor Domitian’s reign around 90 AD, Praetorian soldiers earned 1,500 denarii annually—a fortune that only amplified their sense of entitlement and political ambitions.

Alas, the Praetorian Guard’s influence wasn’t timeless. By 284 AD, their star had dimmed: stripped of privileges guarding the inner sanctum of the Emperor’s residence and eventually replaced by the Scholae Palatinae—a cavalry unit mostly recruited from Germanic tribes—which notably showed less political scheming.

The Varangian Guard: Foreigners with No Ax to Grind

Shift gears to the Varangian Guard, an elite unit born centuries later, around 911 AD, in the Byzantine Empire. Unlike the Praetorians, the Varangians were not locals; they were foreigners—mainly Norsemen (Vikings) and later Anglo-Saxons—hired as mercenaries.

Now, why is it important that they were foreigners? Because they lacked local political ties, kinship networks, or social ambitions embedded in the Byzantine capital. Their mission was simple: protection of the Emperor and enforcing imperial authority without personal political stakes.

Imagine they were like the ultimate independent contractors. Their loyalty was bought with solid pay and the promise of honor, not tangled webs of intrigue or factional games. This mercenary model drastically reduced the incentive to meddle in politics or play kingmaker.

The Varangians fought for over 350 years in Byzantine service. Countless emperors relied on them to stay loyal and effective, especially given internal threats and foreign invasions. The Emperor needed a reliable buffer against court intrigue and domestic treachery, and the Varangians filled this niche perfectly.

What Set Them Apart? The Importance of “Outsider” Status

Recall the historical example of the Batavian men, considered direct ancestors of the Varangians in spirit if not form. These soldiers cared little about Roman internal strife, focusing solely on duty. The Varangians inherited this approach—a no-nonsense, no-political-baggage attitude.

This contrasts sharply with the Praetorians, who were deeply invested in Roman political society. Their “local” status meant they had friends, family, resources, and ambitions tied to Rome’s rising and falling factions. This proximity made them both participants and players in power struggles.

Meanwhile, the Varangians’ foreign roots and mercenary pay tied their fortunes directly to the Emperor’s favor rather than any local group or political faction. Their motivation was simpler—do your job, keep the Emperor safe, and get paid. No drama, no disrupted empires.

Lessons from The Past: Why Does This Matter Today?

This comparison between the two guards offers timeless lessons on the dangers and benefits of elite military units tied closely to power centers.

- The problem with local ties: When a military unit comes from the ruling city or nation’s elite, it might develop its own agendas, using armed status to influence politics and even overthrow leadership.

- The advantage of foreign mercenaries: Employing foreigners with fewer local ties as protectors often means more straightforward loyalty based on pay and duty—not political expediency.

- Balance is key: Too much access and power without oversight can rapidly corrupt elite guards; incorporating outsiders can insulate leadership but risks alienating the populace.

So, the ancient Roman emperors’ mistake was trusting a local army unit that became overly politically ambitious, while Byzantine rulers wisely hired foreigners who had less to gain from political meddling.

Can Today’s Leaders Learn From This?

Absolutely. Consider modern elite forces and bodyguards who might be subject to internal politics. Maintaining their loyalty should involve more than just pay—it should address structural incentives.

Are they too close to the political center? Could that proximity breed ambitions at odds with their protective role? These questions are as relevant now as they were in ancient Rome and Byzantium.

Additionally, as the Varangians show, sometimes recruiting trusted outsiders can reduce risks of internal betrayal. However, this needs balancing with cohesion and trust.

Final Thoughts

The Praetorian Guard’s story is a cautionary tale about how proximity, privilege, and citizenship can corrupt an elite force into kingmakers, turning protectors into power brokers. By contrast, the Varangian Guard’s foreign mercenary status, lack of local ties, and clear contractual loyalty limited political interference, ensuring steadfast service.

Next time you think about elite guards, ask yourself: Are they genuinely loyal to the leader, or merely to their own ambitions? Because history tells us that the closer the guard is to power without checks, the more dangerous they become.