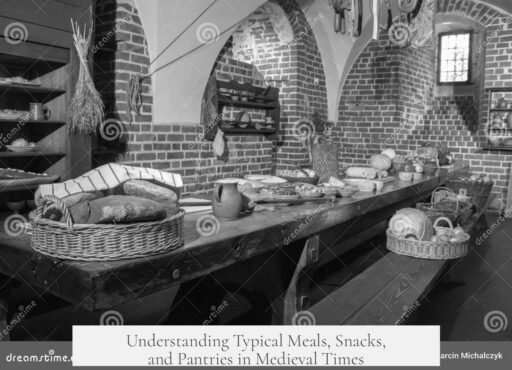

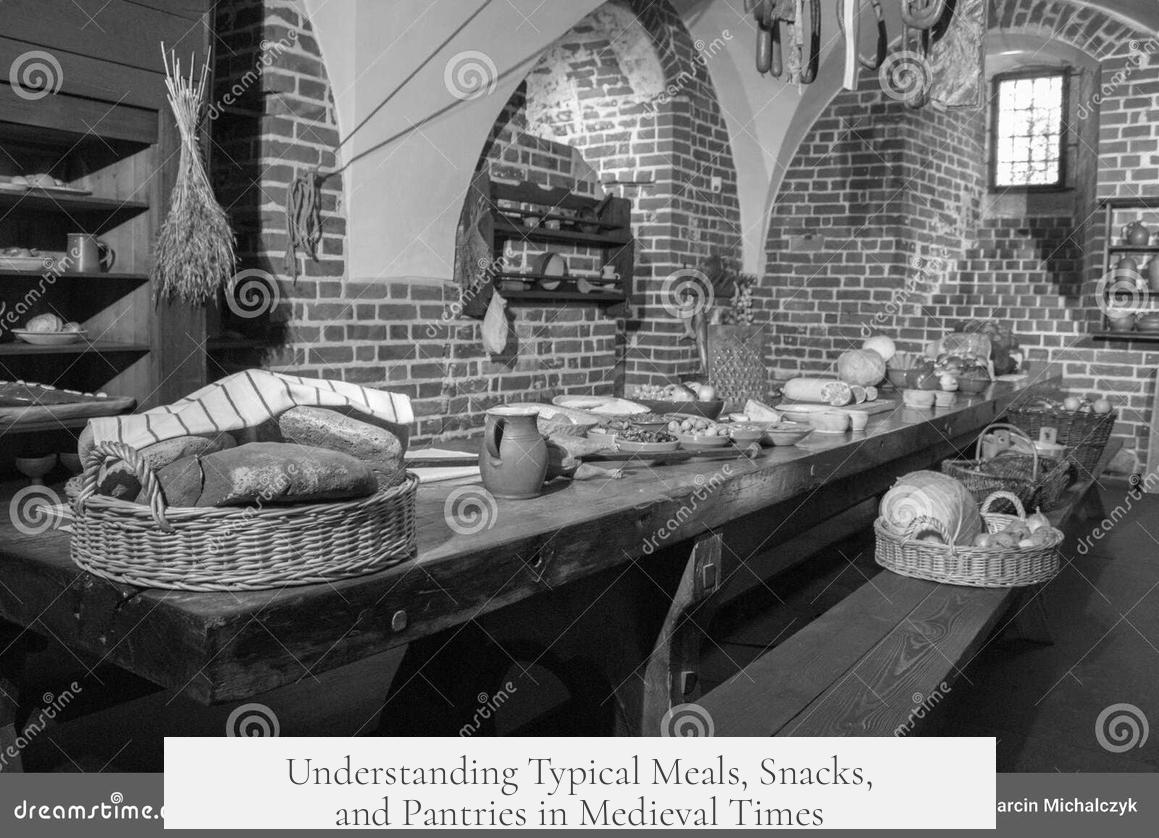

A typical medieval meal, snack, or pantry reflects strong social class influences and the practicalities of the time. Common diets, especially for peasants, consisted mainly of grains, legumes, seasonal vegetables, and occasional proteins such as fish or poultry. Meat was scarce for lower classes, while ale and bread were dietary staples.

In the European Middle Ages, diet varied sharply by social standing. Peasants consumed mostly plant-based foods and grains, with modest protein sources like beans or fish. Ale, often low in alcohol, was frequently drunk, sometimes up to a gallon daily. Variability in harvests caused nutritional gaps, and availability depended heavily on the season.

Grains provided a large part of daily calories. Wheat, rye, oats, and barley were used in three ways:

- Boiled whole into thick soups or stews

- Ground into flour for bread-making

- Malted and brewed into ale

Protein came from legumes such as peas, lentils, or beans. Fish was an occasional but important source, especially in areas near rivers or the sea. Meat, including beef, pork, or poultry, was rare and often reserved for special events. Chickens were more common among peasants, as they were easier to keep and viewed as lower-value livestock.

A prosperous 14th-century English peasant might eat around 2 to 3 pounds of bread daily, along with 8 ounces of meat, fish, or other proteins. They also consumed 2 to 3 pints of ale. Dairy items like eggs, butter, and cheese often substituted for meat. Staple vegetables included onions, leeks, cabbage, garlic, turnips, parsnips, peas, and beans. Seasonal fruits added variety.

Social restrictions influenced diet and food procurement:

- Peasants often lacked hunting rights. This limited access to game meat.

- Fishing was sometimes prohibited but had more exceptions.

- Pigs and cattle were often given to nobles or the church, limiting pork and beef in peasant diets.

- Salted or fermented herring was a widely consumed fish across Europe due to abundant fishing grounds.

Food preparation and preservation were basic. Rural villages lacked modern kitchens or ovens. Fish was kept alive in tanks until eaten to maintain freshness. Spices were scarce or absent for most peasants. Pepper was a rare luxury but often used to mask the taste of food nearing spoilage.

Cooking fires were unpredictable in temperature. People adjusted cooking by experience rather than precise control. Pebbles or ashes helped control heat, but outcomes varied. Bread and porridge were staples because of their simplicity and storage qualities.

Snacks as understood today were uncommon. Meals centered on hearty bread or porridge with vegetables and legumes. Leftover bread might serve as a quick snack. Fruits in season or nuts when available also provided occasional snacks.

Some common medieval pantry items included:

| Category | Common Items |

|---|---|

| Grains | Wheat, Rye, Barley, Oats |

| Legumes | Beans, Peas, Lentils |

| Vegetables | Onions, Leeks, Cabbage, Turnips, Parsnips, Garlic |

| Protein | Poultry, Fish (e.g., herring), Eggs, Cheese, Butter |

| Preservation | Salted Fish, Live Fish Tanks, Smoked Meat |

| Beverages | Ale (low alcohol), Small Beer |

Popular misconceptions exaggerate medieval diets. They are neither exclusively carnivorous nor utterly meatless. Food access depended on status and geography. City dwellers had better access to spices and butchers compared to rural peasants.

Overall, medieval meals were functional and seasonal. Grains and legumes formed the backbone, supplemented with modest protein and fresh or preserved vegetables. Ale was the common drink, often safer than water. Spices were rare outside wealthy households.

- Diet varied greatly by social class, geography, and season.

- Peasants ate mostly grains, legumes, vegetables, and occasional small amounts of meat or fish.

- Richer peasants could afford more protein and dairy products.

- Food preservation was primitive, relying on live fish tanks, salting, and smoking.

- Ale was a staple beverage, low in alcohol but consumed in large quantities.

- Spices were limited and mostly reserved for the wealthy.

What Is a Typical Medieval Meal, Snack, or Pantry Like?

If you’re wondering what a medieval meal looked like, the answer varies greatly depending on your social standing. The Middle Ages were not exactly the era of gourmet dining for all. Whether you were a humble peasant or a noble lord dictated what landed on your plate.

But let’s dig into the real deal of medieval food — the types of meals, snacks, and pantry staples typical for everyday folk, especially peasants, who made up the vast majority of the population.

Medieval Meals Are Mostly About Social Class

Here’s the kicker: your wealth and rank in society shaped your diet profoundly. While the rich feasted on roasted meats and exotic spices, peasants ate simpler fare. We often picture medieval meals as endless meat platters with ribs and game, yet that’s a bit of a myth. In reality, meat was scarce for peasants and reserved for special occasions.

How much ale did they drink? Quite a bit! Estimates show peasants drank up to a gallon a day—though the alcohol level in ale was low. Ale was safe to consume compared to water, which was often contaminated. Think of it as their “hydration and mild buzz” drink combo.

The Peasant Plate: Grains, Legumes, and What They Could Get

For most peasants, grains formed the bedrock of every meal. Wheat, rye, barley, and oats were boiled into soups or pottages, ground into coarse flour for bread, or malted to brew ale.

Protein? Mainly legumes like peas, beans, and lentils. Fish showed up when available, especially herring—a hugely important animal protein across Europe given its abundance in northern fishing grounds. Meat from poultry, pork, or beef was a rarity, often saved for feasts or special times.

Vegetables such as onions, cabbage, garlic, turnips, and parsnips added vitamins and variety. Fruits appeared seasonally—fresh or dried for preservation. However, seasonal changes in food availability meant long lean stretches during poor harvests. Nutrition wasn’t always reliable, even if by today’s standards peasants had relatively decent diets overall.

When a Peasant Gets Prosperous: A 14th-Century Case Study

Imagine a prosperous English peasant in the 1300s. Daily, they likely consumed about 2-3 pounds of rye, oat, or barley bread, along with 8 ounces of meat or fish. Not a steak every day but more like eggs, butter, or cheese substituting for meat most times.

They washed it down with 2-3 pints of ale. Onions, leeks, beans, peas, garlic, and cabbage were their trusty veggies, while fruits came and went with the seasons. Even the more modest peasants had bits of variety compared to the stereotypical “all porridge, all day” idea.

The Medieval Pantry: Cooking, Preservation, and Spices

Cooking and food storage were pretty basic in village life. No modern ovens or fridges—just open hearths and guesswork with fire temperatures. Imagine cooking something with no clue if the flames were 300 or 700 degrees! Fish tanks were actually common to keep fish fresh since refrigeration was science fiction.

Spices were hardly a village staple. Pepper, however, earned a reputation—not so much for flavor but for hiding “funky” tastes in food that was on its way out. Dining at a noble’s table? You’d see an array of spices, but for peasants, this was a rare luxury.

Rights, Restrictions, and the Hunting Problem

Peasants had few rights to hunt game, which was often reserved for the nobility and church. Fishing rules varied, with more exceptions allowing peasants to fish from ponds or rivers but often with limits. This lack of hunting, and significant tithes requiring peasants to hand over their cows and pigs, further limited meat consumption.

Chicken was more commonly available. It was considered a lower-status meat, so peasants could access it more than beef or pork, which were often requisitioned by landlords.

Snacks and Odd Bites: The Medieval Between Meals

Medieval snacks? Not quite like modern chips or candy bars. Peasants might nibble on fruits picked fresh or dried nuts and seeds. Leftovers from the pottages or small yeast-based bread bits were probably common quick bites. Ale could serve as a “snack drink” during work breaks too.

What about something sweet? Honey was precious and expensive, so it appeared mostly on special occasions. Sugar was almost unheard of for peasants.

Changing Our View: Beyond the Renaissance Fair and Myths

Popular culture likes to paint medieval folks either as constant meat-gorging carnivores or starving vegetarians. Both extremes miss the nuance. The reality was complicated by class, geography, season, and local customs.

Yes, peasants’ meals were humble but not without variety or nutrients. No, they didn’t snack on turkey legs at every turn. Yes, ale was their mainstay for hydration.

Next time you watch a Renaissance fair and see the food spread, remember: the typical medieval meal was probably a humble bowl of pottage, some rye bread, a splash of ale, and perhaps a small serving of fish or a few beans. Sounds quite… practical, doesn’t it?

What Can We Learn From Medieval Meals Today?

- Seasonality matters: Medieval people ate what was available each season, a practice worth revisiting for health and sustainability.

- Simple carbs and legumes: Grains and pulses formed a healthy, balanced base for meals.

- Resourcefulness: Limited means didn’t stop them from crafting nutritious meals.

- Food preservation ingenuity: Using fish tanks and drying techniques to keep food edible longer.

So, if you want to replicate a medieval meal, start with hearty rye bread, a bowl of pea or lentil soup, some pickled or salted fish, and wash it down with a mild ale brewed to low alcohol. Maybe you’ll feel a bit like a medieval peasant—but with better kitchen gadgets.

Would you dare try living on a medieval diet for a week? Could modern foodies survive without spices or fast food? Food for thought, indeed.