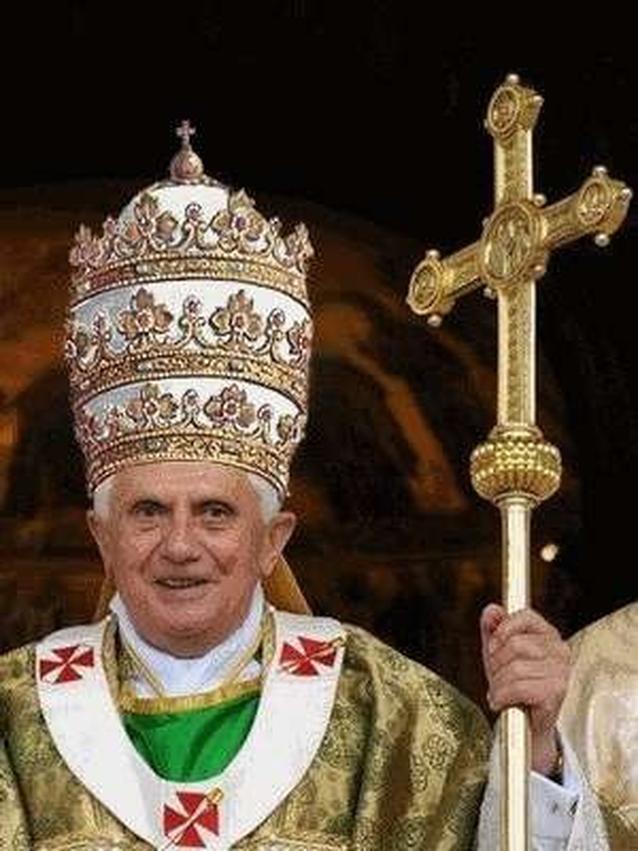

The power of the popes evolved greatly over time, shifting from spiritual leaders with limited influence to potent political figures controlling territories and influencing kings, before gradually fading with the rise of nation-states. Their power had both spiritual and temporal aspects, peaking during the medieval period and diminishing after the 17th century.

At the beginning, the popes were primarily bishops of the Christian community in Rome. This position did not grant significant power early on. During the Roman Empire, especially before Christianity became legal, popes often faced persecution. For example, Peter, traditionally considered the first pope, was martyred around 64 AD after the fire of Rome. The early papacy was fragile and mostly limited to religious guidance within the Christian community.

From the 3rd century, popes began to claim greater spiritual authority. They referred to themselves as successors of Peter, the apostle. The Edict of Theodosius in 380 AD legally established Christianity as the Roman Empire’s religion and gave the pope a form of spiritual primacy. However, this primacy was “primus inter pares”—first among equals—within the early Church. Politically, popes remained subordinate to emperors or local rulers who succeeded each other in Italy, including the Herulians, Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Franks.

The significant rise in papal temporal power came with the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800 AD. By crowning a king as Roman Emperor, the pope claimed the authority to confer imperial legitimacy. This event marked a transfer of power symbolized as “Translatio Imperii,” the transfer of imperial authority to Western Christendom via the pope. Afterward, Holy Roman Emperors required papal coronation to claim legitimacy. This bolstered the pope’s influence beyond religious affairs to political realms, as popes sought supremacy over kings and emperors.

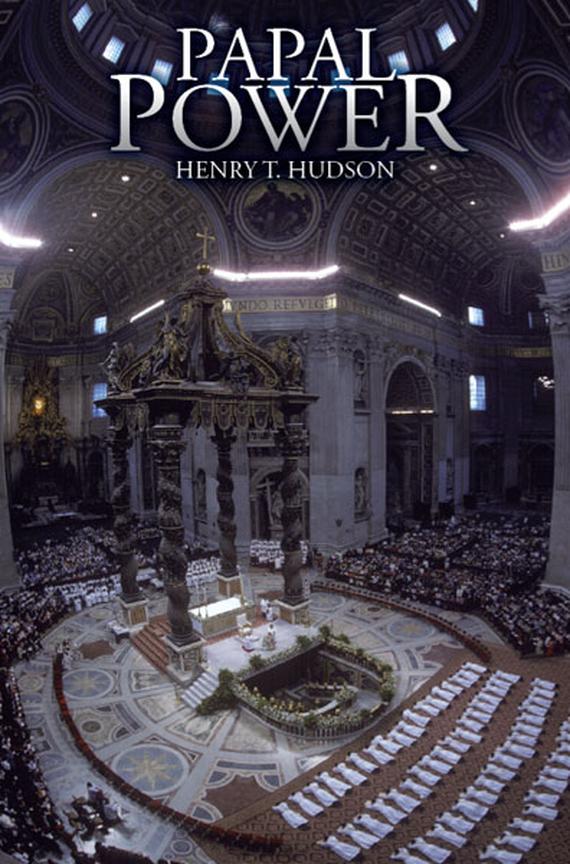

Popes also exercised hard power through control of the Papal States in central Italy. Beyond spiritual leadership, they wielded military and political force by forming alliances, including leagues of Italian states, to resist imperial control. Notable popes like Gregory VII and Alexander III defended papal independence and expanded influence through such means.

The zenith of papal power emerged during Innocent III’s papacy in the early 13th century. He dominated European politics, influencing the appointment of monarchs and making several states papal vassals. Innocent III expanded the pope’s reach to encompass both religious and secular governance, marking the apex of medieval papal authority.

The papacy’s power waned during the Avignon Papacy (14th century), when popes resided in France and were perceived as French king puppets. This weakened papal independence and authority. The Renaissance saw the popes strengthen their temporal control once again by centralizing the Papal States and forming Holy Leagues to counter Ottoman Turks, Protestant movements, and powerful kings. Popes like Julius II and Paul III played significant roles in diplomatic and military efforts.

However, the rise of nation-states greatly diminished papal power. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) ended the Thirty Years’ War with state sovereignty, critical of papal mediation and rejecting its role in European politics. The papacy’s last major temporal victory was the Holy League defeating Ottoman forces at Vienna in 1683.

Pope Urban II demonstrated papal influence through spiritual authority by launching the First Crusade in 1096. His call mobilized nobles and peasants alike, highlighting the pope’s power to absolve sins and inspire religious warfare. This spiritual authority was pivotal in rallying large segments of society.

Over time, papal temporal power declined, partly due to the assertion of independent monarchies in France, England, and Germany. The Western Schism further eroded papal unity and authority. By the early modern period, popes retained primarily spiritual leadership with much reduced political sway.

| Period | Papal Power Highlights |

|---|---|

| Early Church (1st-2nd Century) | Spiritual leadership; faced persecution; limited influence |

| 3rd-4th Century | Spiritual primacy in Church recognized; under imperial authority |

| 800 AD | Charlemagne crowned; pope gains role in imperial legitimacy |

| Middle Ages (12th-13th Century) | Control over Papal States; military alliances; peak under Innocent III |

| 14th Century | Decline due to Avignon Papacy and Schism |

| Renaissance | Return to Rome; formation of Holy Leagues; political renewed vigor |

| 17th Century Onward | Decline with rise of nation-states; Treaty of Westphalia as a turning point |

- Popes began as local bishops with limited power but gained spiritual authority by the 4th century.

- The coronation of Charlemagne enhanced papal political importance and claim to temporal power.

- Popes controlled the Papal States; they wielded military and political influence in Italy and Europe.

- Innocent III marked the height of papal power, influencing kings and European politics deeply.

- Later periods saw decline due to rival monarchies, the Avignon Papacy, and church schisms.

- Despite fading political power, popes maintained spiritual roles and occasionally formed military alliances.

- The rise of nation-states and the Treaty of Westphalia largely ended papal temporal authority.

How Powerful Were The Popes? Unveiling the Layers of Papal Power Through History

Short answer: The power of the popes evolved dramatically over the centuries—from vulnerable community bishops to influential spiritual leaders, to formidable rulers with armies and kings bowing to their authority. But let’s unpack that journey step-by-step, because the tale of papal power is anything but straightforward.

Imagine this: the early popes were more like community shepherds than the grandiose religious emperors we often picture. Initially, bishops in Rome were not powerhouses—far from it. In fact, persecution awaited many early Christians, including Peter himself, who “graduated” from bishopric duties in 64 AD under less-than-kind circumstances. Very cool, divine martyr but hardly the portrait of power.

From Persecuted to Prized: The Rise of Spiritual Authority

Fast forward to the 3rd and 4th centuries. The Roman Empire is big, complicated, and Christianity is slowly turning from an underground faith to the official family religion. During this time, popes start casting themselves as successors to Peter, bolstering spiritual clout. When Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity, the popes got a juicy upgrade—financial perks and more respect.

The 380 AD Edict of Theodosius gave Christianity the legal nod and specifically praised the bishop of Rome. This wasn’t just a “nice job” card; it was a *primacy* within the Church. Yet, remember this: it was spiritual primacy, not political dominance. The pope was still under the thumb of emperors. Think of him as the spiritual CEO working under a very powerful political boss who wore a crown, and later, a robe made from questionable fabrics from various invaders like the Goths and Lombards.

When Spiritual Influence Meets Political Muscle: Charlemagne’s Coronation

In 800 AD, Pope Leo III crowns Charlemagne emperor, and history shifts on its axis. This isn’t just a ceremonial hat placement—it’s a declaration: the Pope now claims a share of temporal power. Europe listens. From this point, Holy Roman Emperors need the pope’s stamp for legitimacy. It’s like getting your diploma signed by the headmaster of the school of kings.

This moment opens the door for the Papacy to assert supremacy over secular rulers—not just spiritual leaders. Suddenly, popes don’t just bless kings; they become kingmakers. That’s a fancy, powerful role in medieval politics.

Hard Power: The Papal States and Military Influence

Of course, power isn’t all about handshakes and blessings. The popes actually ruled territory—the Papal States. They wielded armies, built alliances, and threw their weight around on the battlefield. Whether it was partnering with northern city-states or southern duchies, the Pope could flex serious muscle. Popes like Gregory VII and Alexander III showed just how formidable the Papacy could be when it came to realpolitik.

The Medieval Boom: Innocent III at His Peak

Meet Innocent III—the pope who looked at Europe and pretty much said, “You’re mine.” His influence peaked in the early 13th century when many European monarchs didn’t just respect the pope; they owed their crowns to him. Some rulers became papal vassals, stretching the Pope’s reach across kingdoms and courts.

This broad power wasn’t just symbolic. It meant serious control over political affairs in Europe, shaping laws, wars, and alliances.

Facing Challenges: Decline During the Avignon Papacy

But every high has its low. The Avignon Papacy (1309–1377) marks a wobbly phase in papal power. The popes didn’t even live in Rome—they were in France, effectively under King Philip’s thumb. This made the papacy look less like divine authority and more like royal puppetry. Oops.

A Renaissance Revival: Holy Leagues and Political Games

The popes came back to Rome and rebuilt their strength during the Renaissance. They organized “Holy Leagues,” which were coalitions of European monarchs. These alliances aimed to curb Protestant movements, defend against Ottoman Turks, and check the ambitions of over-zealous kings.

Popes like Julius II, Paul III, Pius V, and Sixtus V showcased this renewed practical power. Not everyone was as adept—Alexander VI, with his infamous reputation, was less about power and more about personal scandal.

Urban II and the Power of Spiritual Motivation

One of the most striking displays of papal power was Pope Urban II’s call for the Crusades. During his famous 1096 speech, he roused knights and peasants alike to march to the Holy Land. This illustrates the pope’s tremendous influence—not just over kings, but even common folk obsessed with sin and salvation.

Urban’s ability to absolve sins was like having ultimate spiritual VIP access. Want forgiveness? The pope held the keys. This power translated into masses willing to risk their lives on crusades. When your religious leader calls you to battle with promises of absolution, power isn’t just spiritual—it’s social and military.

The Slow Fade: Rise of Nation-States and the Treaty of Westphalia

The papacy didn’t remain atop forever. Growing nation-states like France, England, and Germany began to resist papal authority, especially as monarchs claimed sovereignty. The Great Schism (split in the Church) weakened the pope’s influence further.

The final nail? The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. This treaty ended the Thirty Years’ War and rejected the pope as a European mediator. It marked the rise of modern nation-states asserting themselves independently. Yet, the pope still managed one last significant role in 1683 with the Holy League defending Vienna from Ottoman sieges. Not bad for a fading star.

A Complex Legacy of Power

So, how powerful were the popes? They were spiritual shepherds, game-changing kingmakers, territorial rulers, military leaders, and moral arbiters. Their power is a story of constant evolution—shaped by politics, faith, and circumstance.

From humble origins and persecution to crowning emperors and commanding armies, the popes’ influence has waxed and waned with history’s tides. Would today’s popes regain such temporal clout? Probably not—but their role as global spiritual symbols remains undeniable.

Curious How This Shaped Today?

The historical buildup of papal power helps explain modern interactions between church and state. It reminds us that spiritual authority can morph into political force. And it invites us to wonder—how would a spiritual leader wield power in today’s world? Would they crown kings or lead coalitions against unexpected foes?

Whatever your take is, the story of papal power is a testament to the dynamic interplay between religion, politics, and human ambition.