The South was not destined to lose the Civil War from the very beginning, but numerous factors heavily favored the North, making Southern defeat highly likely. The Confederacy faced critical disadvantages in resources, manpower, strategy, and diplomacy that gradually eroded its capacity to sustain the war. However, a few turning points and leadership decisions could have altered the conflict’s course.

One key reason the South struggled was its defensive military stance combined with inferior infrastructure and resources. While defending familiar terrain provides advantages, the Confederate states lacked the industrial base to produce sufficient arms, ammunition, and supplies. The North’s capacity to wage war on multiple fronts with greater logistics was decisive. The South hoped to endure until Northern morale faded, but this proved unrealistic.

General Robert E. Lee’s decisions shaped many critical campaigns. If Lee had launched an early northern invasion, it might have shifted public opinion in the North by showing the war’s heavy cost on their soil. Yet this risked uniting Northern support more firmly. The failure to capitalize on lost Union orders before Antietam exemplifies how luck and small mistakes cost the South momentum. Likewise, Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville removed a key adviser whose counsel was crucial at Gettysburg. These missed opportunities highlight how leadership affected outcomes.

Foreign intervention was another potential lifeline for the South. Britain and France disliked slavery but considered supporting the Confederacy due to cotton shortages. The South’s inability to secure this help, especially after Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation, sealed the diplomatic fate. The North’s moral stance helped keep European powers neutral, denying the Confederacy critical military and economic aid.

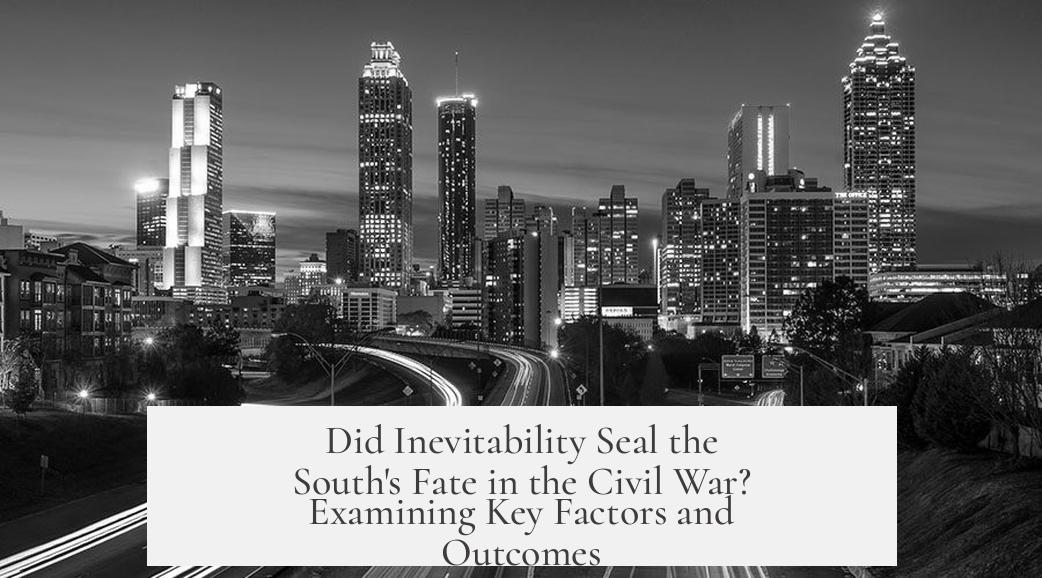

| Factor | South’s Situation | North’s Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Capacity | Limited factories, dependent on agriculture and slavery | Massive industrial output, armaments production |

| Economic Resources | Dependent on cotton exports, weak economy | Strong, diversified economy, capable of prolonged war |

| Manpower | Smaller population, loss of enslaved labor, internal dissent | Larger population and recruitment, including freed slaves |

| Military Strategy | Primarily defensive with inferior infrastructure | Offensive strategy, better supply lines |

| Diplomacy | Failed to secure European support | Maintained foreign neutrality |

The South’s economic structure resembled a colonial economy reliant on cotton and slave labor. The Northern industrial economy and rail networks allowed the Union to implement the Anaconda Plan effectively. This strategy strangled Southern ports, crippling the South’s trade and access to critical supplies. Rhett Butler’s assessment underscored this reality: the North was equipped with factories, shipyards, and a fleet to enforce blockades, while the South relied on cotton and slavery, plus overconfidence.

Internal challenges added to Southern difficulties. Many enslaved people escaped or rebelled, which diminished labor and created unrest. Not all Southerners supported secession or the Confederacy, causing division. Moreover, strong states’ rights traditions hampered unified command and centralized logistics, weakening the war effort. Poor manufacturing capacity and manpower shortages compounded these problems.

Political will shaped the war’s trajectory. The North’s determination and capacity to replenish forces contrasted with Southern hopes to erode Northern resolve through attrition. The Confederacy’s realistic chance rested in achieving a political victory by inflicting enough casualties to force negotiation. The shift in Union leadership and replacement of generals sometimes influenced the war’s course, as seen in Atlanta’s 1864 campaign, which impacted Northern election politics.

In conclusion, while a few strategic changes or fortuitous events might have improved the Confederacy’s prospects, the overwhelming industrial, economic, and demographic advantages of the North, compounded by diplomatic failures and internal fragmentation in the South, made Southern defeat highly probable from an early stage.

- The South’s limited industrial base and reliance on slavery weakened its war capacity.

- Leadership decisions and missed opportunities critically affected key battles.

- Failure to gain foreign recognition or aid disadvantaged the Confederacy.

- Internal dissent and states’ rights conflicted with wartime unity and logistics.

- The North’s superior resources, manpower, and resolve ensured its likely victory.

Was the South Destined to Lose the Civil War from the Beginning?

The South was, in many ways, destined to lose the Civil War from the start. But hold on—this isn’t just a simplistic case of “South was weaker, so they lost.” The reality is far richer, filled with strategic choices, missed chances, economic factors, and political realities that intertwined into a complex tapestry of eventual defeat. So, let’s unpack why the South faced uphill battles, both literal and figurative.

First off, let’s talk about military strategy and leadership. The South mainly fought a defensive war with fewer resources and poorer infrastructure. Fighting defensively with limited resources sharply reduced their chances. They had to hold ground against the Union’s industrial and numerical firepower. And unlike the North that could replenish forces and supplies easily, the South had to make every soldier and bullet count.

General Robert E. Lee, who became the South’s shining light, made some questionable strategic calls. What if Lee had taken the war north earlier, attacking Union soil? Could that have led to the North losing heart and saying, “Eh, let them go”? Possibly. But it’s equally possible that a Southern invasion would have galvanized the North even more. It’s a historical “what-if” with no clear winner in speculation.

Imagine Lee—and his intimidating movement of troops—marching into Pennsylvania in 1861 or 1862. Would Northerners pack up their troubles, or pick up their rifles harder?

One critical moment was the loss of “Special Orders 191,” a set of Confederate battle plans supposedly dropped and found by Union forces. If that had never happened, Antietam might never have become the bloodiest single-day battle that stalled Lee’s advance. That tie score at Antietam gave Lincoln the opening to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, pushing the war onto moral ground and keeping Europe from siding with the South.

Speaking of battles, Lee’s failure at Gettysburg was a turning point. This loss crushed one of the last hopes the South had to seriously challenge the North’s strategic advantage. And what if Stonewall Jackson hadn’t accidentally been shot by his own men after the Battle of Chancellorsville? His military advice and partnership with Lee could have changed the battlefield dynamics—Jackson was Lee’s trusted lieutenant, and his absence was deeply felt.

Later in the war, leadership choices impacted the outcome. President Jefferson Davis replaced General Joseph E. Johnston with John Bell Hood during the Atlanta campaign. Hood was aggressive but reckless, leading to severe losses. Had Johnston stayed, and maintained a defensive grip, it’s conceivable war weariness might have forced the North into seeking peace. Maybe McClellan’s election instead of Lincoln could have ended the war earlier or in a settlement favorable to the South.

External Factors and Diplomatic Hopes

The Confederacy banked heavily on possible foreign intervention from Britain or France. Those powers might have shifted the balance by recognizing the South or even sending aid. However, foreign governments strongly opposed slavery, and the North’s Emancipation Proclamation gave them moral cover to stay out. So, with cotton as their main economic card and no foreign hands dealt, the South’s diplomatic hopes were slim.

It’s also worth noting that the stalemate at Antietam played a pivotal role here. Without that bloodied draw, the Union wouldn’t have claimed the Emancipation Proclamation’s moral high ground. Without this, Britain and France might have found a reason to recognize the Confederacy. Timing really is everything.

Economic and Resource Disparities

Let’s talk money and manpower—two critical war ingredients the North had by the truckload. The North had industrial capacity capable of manufacturing weapons, ships, railroads, and everything else a modern war machine needed. The South? Not so much. Their economy heavily depended on cotton exports, with about a third shipped to the North, which was ironically supporting the Union war effort.

Rhett Butler’s plain assessment nails it: “Yankees are better equipped than we. They’ve got factories, shipyards, coal mines… and a fleet to bottle up our harbors and starve us to death. All we’ve got is cotton, slaves, and… arrogance.”

Indeed, the South had a colonial-style economy that pivoted mainly on slave labor and agriculture. Modern industrial work, like factory labor or railway management, wasn’t embraced by the plantation elite. This created logistical nightmares. The North’s railroads and industries ensured supplies could move efficiently. The Anaconda Plan—which blockaded Southern ports and squeezed the South’s resources—became nearly impossible for the Confederacy to resist.

Internal Societal Issues and Political Will

Manpower was another ticking clock. Southern logistics were poor, manufacturing capacities were limited, and the state’s rights ideology frequently hampered a unified war effort. The Confederacy often struggled to coordinate its armies as states jealously guarded their autonomy, a political patchwork that made central command difficult.

On top of that, many enslaved people resisted in various ways—escaping, rebelling, or simply disrupting plantation economies. Not every Southern citizen wanted to secede, which added to internal tensions. In contrast, the North had a clear motive: preserve the Union, and eventually, end slavery.

And here lies the fundamental difference, the stubborn political resolve. The North was prepared to fight until victory, bolstered by growing political will and industrial stamina. The South’s best hope was purely political: to inflict enough casualties and undermine Northern resolve so that a favorable peace could be negotiated.

Unfortunately for the South, this strategy only worked if the North tired of war quickly. But initial Southern victories like Bull Run and Chancellorsville didn’t break Northern spirits as hoped; they only deepened the resolve. By 1864, the North’s leadership, industrial base, combined with an expanding pool of fighters (including liberated slaves), overwhelmed Confederate capabilities.

So, Was the South Truly Doomed?

Looking at all angles—military setbacks, leadership risks, limited resources, diplomatic failures, internal dissent, and overwhelming Northern advantages—it’s difficult to argue the South had a real fighting chance from day one. The Confederate defeat seems almost baked into the cake.

But history isn’t always predetermined. Several incidents, like lost orders or Jackson’s death, highlight how chance and leadership shaped the war’s course. Had a few of those moments swung the other way, the Civil War might have dragged on longer or ended differently. However, the inherent systemic weaknesses and imbalances suggest the South’s ultimate fate was unlikely to be victory.

Did the South lose because it was fundamentally weaker? Yes. Did it lose because of flawed leadership, missed opportunities, and strategic errors? Also yes. Did that guarantee defeat right from the start? Probably. And isn’t that a sobering thought about how grand conflicts can come down to resources, choices, and sheer grit on all sides?

History loves a good underdog story, but sometimes the underdog faces a mountain too steep—even with the best climbers.