Depth charges in WWII were moderately effective but had significant limitations that restricted their overall impact. Their success depended on the accuracy of sensors, explosive power, and deployment tactics. Early in the war, effectiveness was low, improving through technological advances and operational experience.

Depth charges required locating enemy submarines to work. Without precise sonar (Asdic) systems, attacks were largely guesswork. Early Asdic struggled to maintain contact at close range, allowing submarines to evade once escorts closed in. Sonar improvements like the 1943 Q attachment and Type 144 increased target detection sensitivity and helped maintain contact until attack.

Sink rate was critical. Early depth charges sank slowly, giving submarines time to avoid the blast radius. The Royal Navy’s Mark VII sank at 7-10 ft/sec with a lethal radius of about 20 feet, limiting effectiveness. The Mark VII ‘Heavy’ with added cast-iron weight doubled sink speed to 16 ft/sec and increased lethal radius. The Mark X ‘One Ton’ charge was more powerful, sinking faster and with a 2000 lb charge, rivaling patterns of smaller depth charges.

Operational data illustrates depth charge performance. During the first six months of WWII, 4000 depth charge attacks yielded only 33 submarine sinkings (1% success). By 1943, accuracy gains raised this to about 5% success. Attacks increased, with 554 attacks causing 27.5 sinkings by mid-1943. Overall effectiveness remained modest, often requiring saturation attacks from multiple ships.

New ahead-throwing weapons like Hedgehog and Squid improved kill rates. Hedgehog, introduced in 1942, fired multiple contact-fused projectiles and achieved nearly 17.5% success in 268 attacks. Squid mortars, with depth-setting sonar guidance and heavier charges, had an estimated kill rate of 25-40%, greatly outperforming traditional depth charges.

Tactical deployment faced challenges. Depth charges were initially rolled off the stern, limiting range. Improved launchers extended reach to roughly 67-78 yards. Given torpedo ranges of several thousand yards, depth charges required escorts to close dangerously near submarines. This sprint often disrupted sonar contact and provided submarines time to hide or dive deeper, where charges were less effective.

Several factors reduced depth charge lethality. Sensor blind spots, sinking time delay (“dead time”), and submarines diving deeper limited hits. Depth charge explosions often damaged equipment like periscopes and hydrophones rather than causing hull breaches, forcing submarines to surface or retreat. Persistent attacks drained batteries and morale, affecting submarine performance indirectly.

Despite these limitations, depth charges were valuable due to cost and availability. Cheaper than torpedoes or newer weapons, they provided a means for escorts to contest submarines. Even an unsuccessful attack disrupted enemy operations, forcing slower submerged movement. Depth charges helped stabilize convoy defense while more advanced weapons and tactics developed.

| Weapon | Attacks (Period) | Sinkings | Approximate Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth Charges (early WWII) | 4000 attacks (first 6 months) | 33 sinkings | ~1% |

| Depth Charges (mid-1943) | 554 attacks | 27.5 sinkings | ~5% |

| Depth Charges (overall WWII) | 5174 attacks | 85.5 sinkings | ~1.65% |

| Hedgehog | 268 attacks | 47 kills | ~17.5% |

| Double Squid | 27 attacks | 11 kills | ~40.7% |

- Depth charges required accurate sonar to locate submarines, initially a weak point.

- Slow sink rates and small lethal radii limited effectiveness early in the war.

- Technological advances improved kill rates from about 1% to 5% by 1943.

- Ahead-throwing weapons later outperformed depth charges significantly.

- Despite low kill rates, depth charges disrupted enemy operations and were cost-effective.

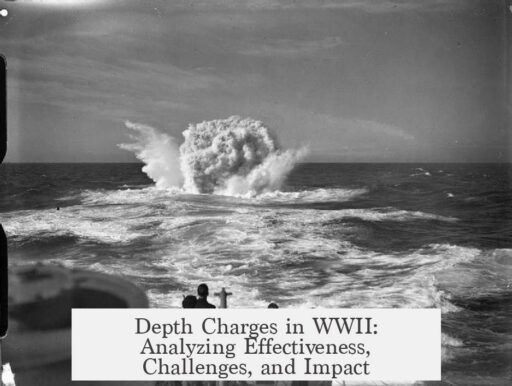

How Effective Were Depth Charges in WWII? An Explosive Dive into History

How effective were depth charges in WWII? The short answer: they started out pretty feeble, like a first-time chef’s soufflé, but improved enough to become a credible threat. Yet, they never turned into the submarine hunters’ silver bullet. Let’s drop into the depths of this subject and unravel the twists and turns of WWII anti-submarine warfare, focusing on the role depth charges played.

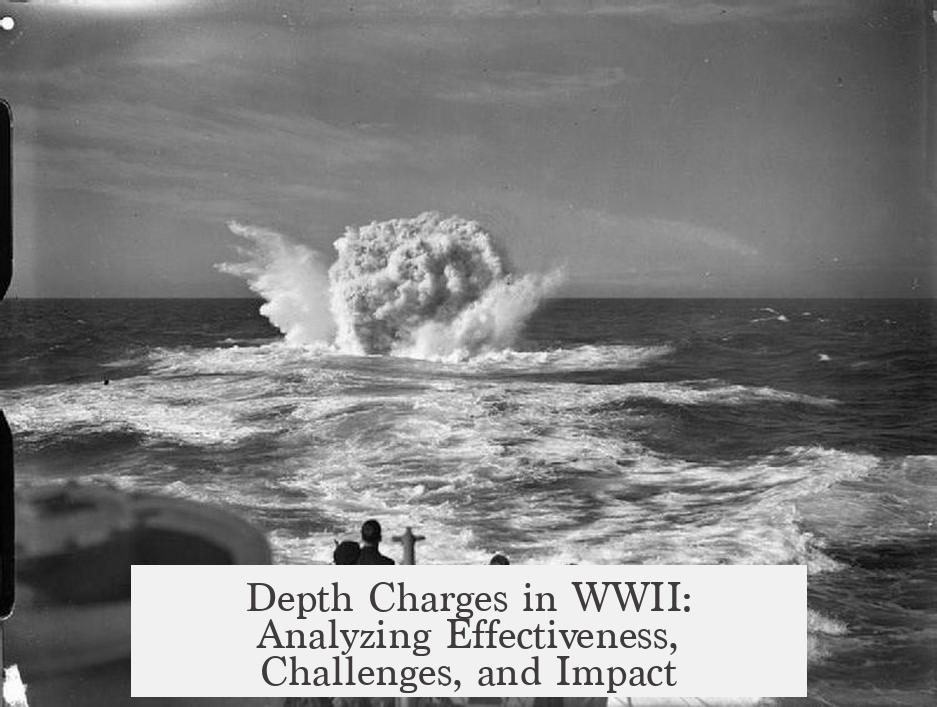

Picture this: It’s 1939. Allied escort ships glide across the stormy Atlantic, hunting elusive German U-boats that threaten vital supply lines. The main weapon in their arsenal? Depth charges—underwater explosives designed to detonate at specific depths and send shockwaves damaging enough to cripple submarines, if not outright sink them.

1. The Triple Threat: Sensors, Sink Rate, and Explosive Power

Depth charges weren’t just exploding buckets tossed overboard. Their effectiveness boiled down to three critical factors. First, locating the submarine—no easy feat without proper sensors like Asdic (the early sonar). Second, how fast the depth charge sank—too slow, and the crafty subs had time to dodge. Finally, the size and composition of the explosive determined the damage radius.

Without advanced sensors, finding a submarine was like trying to spot a stealthy cat in a moonless alley, working blindfolded. Early WWII sonar systems had serious drawbacks, losing contact when the ship closed in, allowing subs to slip away with impunity.

Meanwhile, many early depth charges sank sluggishly at 7 to 10 feet per second. This agonizingly slow descent gave subs a precious window to evade. That’s like dropping a rock in a pond and watching the ripples fade without ever hitting the target below.

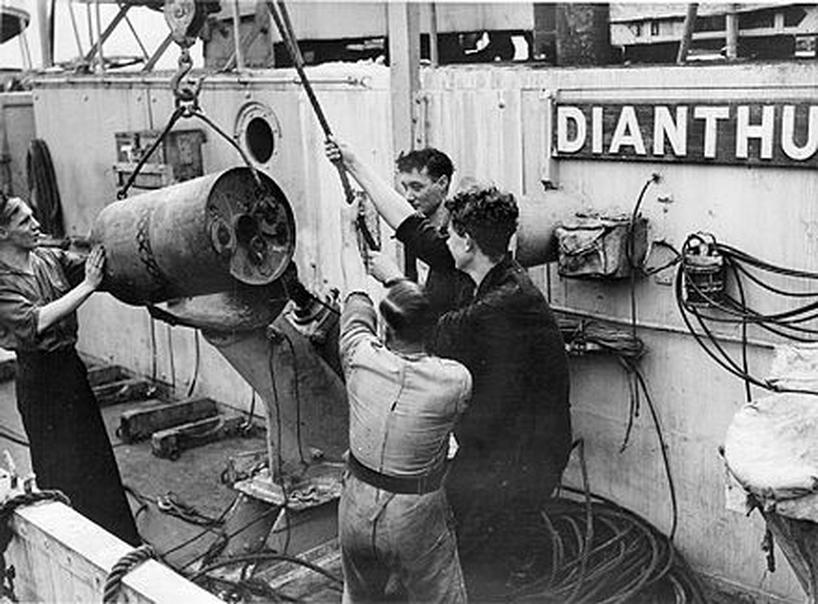

2. Evolution Under Pressure: From Mark VII to the Mighty Mark X

The Royal Navy’s Mark VII depth charge, introduced in 1939 with 290 pounds of Amatol explosive, aimed for a lethal radius of about 30 feet but fell short at 20 feet. And, as we mentioned, a slow sinking rate made it less effective. Equipping ships with these felt a bit like handing soldiers water pistols in a gunfight.

Improvement came with the Mark VII Heavy, which added cast-iron weights to double the sink rate to 16 feet per second. Pair that with a more potent Minol charge, lethal out to 26 feet, and the weapon finally had a fighting chance.

The royal prize was the Mark X or the ‘One Ton’ charge—massive 2000 pounds of explosives, launched from 21-inch torpedo tubes. This beast sank at 21 feet per second and packed the punch of ten Mark VIIs. It was akin to moving from squirt guns to bazookas.

On the sensor front, 1943’s Q attachment and Type 144 Asdic dramatically improved detection and close-range targeting, addressing the Achilles’ heel of earlier lackluster sonar.

3. Counting Kills: The Cold, Hard Numbers

Did all this tech and upgrades translate into battlefield supremacy? Initially, not so much. During the first half of WWII, 4,000 depth charge attacks yielded a meager 33 submarine sinkings—about a 1% success rate. Pretty dismal by any standard.

By 1943, things improved—3 to 5 times so. Depth charges then enjoyed roughly a 5% success rate, with 554 attacks causing 27.5 sinkings (shared kills included). In the war’s final two years, 5,174 attacks led to 85.5 sinkings, roughly 1.65% overall success.

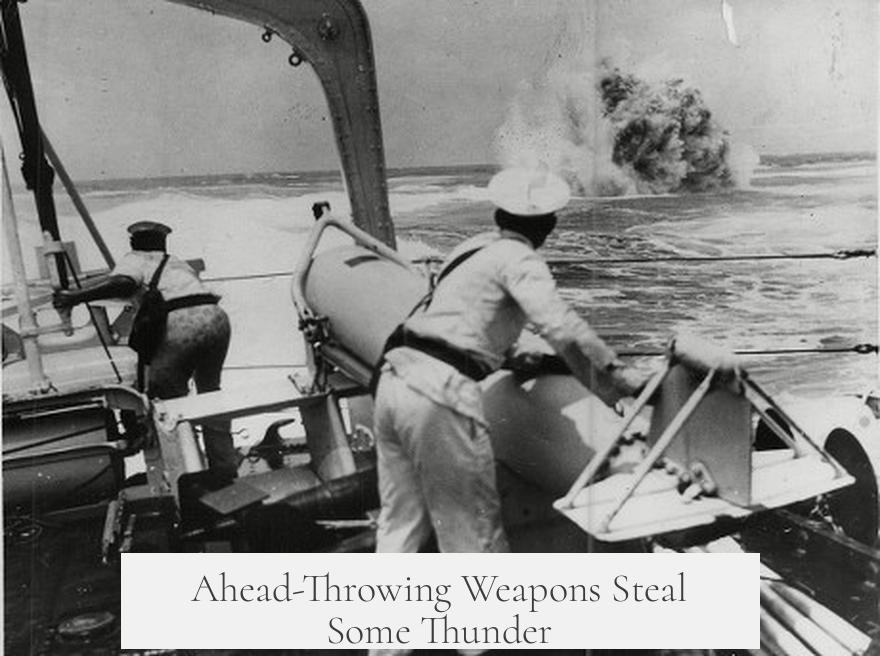

Ahead-Throwing Weapons Steal Some Thunder

Depth charges weren’t the only fish in the sea. The Hedgehog and Squid weapons systems, introduced mid-war, raised the bar. The Hedgehog fired 24 bombs that detonated only on contact and boasted a remarkable 17.5% success rate. The Squid, tying into advanced sonar, had expected success rates north of 25%, with the double version clocking over 40%—numbers that made depth charges look like charming but clunky relics in comparison.

4. Tactical Challenges and Range Blues

Depth charges came with serious limitations. Early on, they were literally rolled off the ship’s stern. With time, throwers extended their range to about 67-78 yards. Compare this to German torpedoes reaching up to 15,300 yards, and you see the challenge.

Submarines commonly engaged targets at around 225-1,000 meters. Allied ships rushed into the attack, often losing sonar contact as their speed degraded sensor feedback. This “sprint” effect essentially blinded the hunters as they closed in.

The usual tactic? Saturating the suspected submarine locale with depth charge patterns—not precision. Imagine throwing a bucket of confetti to catch a fly rather than a targeted swat.

5. Why So Few Kills? Sensor, Tactical, and Technical Snags

The low effectiveness boils down to three big issues:

- Sensor Blinding: Closing in on the sub made sonar inefficient. Escorts often went blind just when they needed eyes the most.

- Submarine Evasion: Subs could dive deeper or maneuver away during the depth charge’s slow sink time, essentially slipping through an underwater magic trick.

- Saturation Weapon Necessity: Depth charges had to be dropped in large numbers, creating an explosion cloud rather than a surgical strike. This made assessing damage and confirming kills complex, especially when multiple escorts and weapons got involved.

6. Beyond the Big Bang: Non-Lethal Effects You Should Know

Depth charges didn’t have to sink a boat to mess with it. Even distant explosions shook and broke periscopes, fouled hydrophones, and stripped subs of their situational awareness. Forced to stay submerged longer to avoid depth charges, submarines drained their batteries, slowed down, and risked falling behind convoy movements.

The psychological toll was real, too. Prolonged attacks rattled crews, fraying nerves and pushing commanders toward mistakes. The silence below decks was often filled with the ominous ticking beats of charging depth charges—and the dread that comes with them.

7. Cheap, Cheerful, and Indispensable

Powered by a simple design and relative affordability, depth charges were an accessible weapon for almost any escort ship. Their cost-effectiveness meant navies could deploy them en masse to guard convoys, even if many failed to deliver lethal blows.

Sometimes, just making a submarine dive deep or break off an attack counted as a victory. In a booking ledger, that’s a “denial,” and it bought valuable time and security for those lifeline convoys crossing the Atlantic.

Summary Table: How Did They Stack Up?

| Weapon | Attacks (Period) | Sinkings (Attributed) | Success Rate Approx. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth Charges | First 6 months (WWII) | 4000 attacks → 33 sinkings | ~1% |

| Depth Charges | Jan-Jun 1943 | 554 attacks → 27.5 sinkings | ~5% |

| Depth Charges | Last two years (WWII) | 5,174 attacks → 85.5 sinkings | ~1.65% (Overall) |

| Hedgehog | During wartime (later years) | 268 attacks → 47 kills | ~17.5% |

| Double Squid | Late war | 27 attacks → 11 kills | ~40.7% |

Final Thoughts: Depth Charges—A Blunt but Valuable Tool

Depth charges were never going to be the equivalent of a sniper rifle in anti-submarine warfare—they were more like a pressure cooker blasting hot steam in all directions.

Their early ineffectiveness stemmed from technological limitations, sensor weaknesses, and the clever evasive tactics of submarine crews. But progressive upgrades to explosives, sink rates, and sonar improved performance. Plus, their low cost and simplicity meant every escort ship could carry them, and their use deterred subs even when not delivering lethal hits.

Combined with ahead-throwing weapons like Hedgehog and Squid, depth charges kept the U-boat threat in check, contributing to the eventual Allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic.

So, next time you see a WWII movie with depth charges dropping like oversized popcorn kernels, remember: they weren’t perfect, but they helped win a titanic underwater chess match. Sometimes, even an imperfect weapon keeps the enemy guessing—and that counts for a lot.