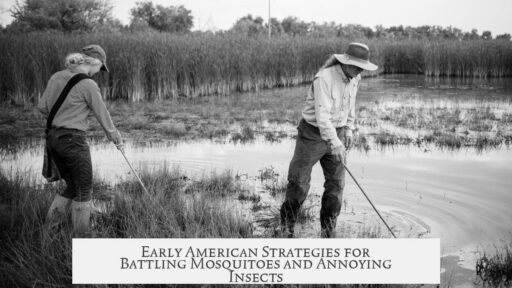

Early Americans managed mosquitoes and other insects through diverse natural methods. They applied plant-based mixtures, animal oils, and smoke to repel or kill pests effectively.

Many Native American groups crafted ointments from local plants combined with animal fats. The Powhatan people used a mix of crushed puccoon and wild angelica roots blended with bear’s oil. This protective ointment guarded their skin from lice, fleas, and other vermin. Similarly, North Carolina Indians used scarlet root mixed with bear’s oil to prevent lice infestations. Cherokee tribes turned to golden seal plant and bear grease as a reliable insect repellent. These oils and mixtures formed a physical barrier deterring biting insects.

Plants from the mint family also played a significant role. Pennyroyal leaves were kept dried in homes to repel fleas, particularly by the Rappahannock Indians in Virginia. They used pennyroyal juice for warding off deer ticks, while dittany worked against horseflies. These plants contain natural compounds toxic or repellent to various insects.

Animal oils provided general protection. Bear’s oil was widely used as a defense against multiple vermin types, including mosquitoes. In New England, indigenous people applied oils from fish, eagles, and raccoons not only to shield against sunburn but also to deter mosquito attacks. These oils served as a protective skin layer.

Smoke was another important remedy. Burning flea banes—herbs from the Erigeron species—helped destroy fleas and gnats by spreading smoke through living areas. Archaeological findings in Florida suggest that smoke screens were used in large meeting halls to keep flying bugs away. Continuous smoke created an inhospitable environment for insects.

| Method | Materials | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Plant-Based Ointments | Puccoon, wild angelica, scarlet root, golden seal mixed with bear’s oil | Repels lice, fleas, mosquitoes |

| Mint Plants | Pennyroyal, dittany | Repels fleas, deer ticks, horseflies |

| Animal Oils | Bear’s oil, fish oil, eagle fat, raccoon fat | Protects skin from sun and insects |

| Smoke | Burned flea banes (Erigeron spp.) | Destroys fleas, gnats; repels flying bugs |

- Early Americans utilized natural plant and animal resources to combat insects.

- Bear’s oil was central to many repellent mixtures.

- Smoke from burning specific herbs helped maintain bug-free spaces.

- Methods focused on creating hostile environments for pests rather than chemical poisons.

How Did Early Americans Deal with Mosquitoes and Other Annoying Bugs?

Early Americans battled mosquitoes and pesky bugs with clever, natural tricks that relied heavily on plants, animal oils, and even smoke. They didn’t have bug sprays or citronella candles but used what nature offered—sometimes with surprising results.

If you’ve ever swatted at mosquitoes on a summer night, you might wonder how people survived without modern repellents. Let’s dive into these historical hacks and see how early Americans kept bugs at bay.

Plant-Based Ointments and Mixtures: Nature’s DIY Bug Repellent

One of the most fascinating early defenses came from Native American tribes, who created ointments from local plants combined with animal oils. Robert Beverly, a colonial observer, noted something quite special about the Powhatan tribe’s recipe:

“Crushing the roots of puccoon and wild angelica, mixed with bear’s oil, rubbed on the skin to ‘conserve the substance of the Body.’ This mixture also kept away ‘Lice, Fleas, and other troublesome vermine from coming near them.’”

Imagine this: a bear-oil based concoction applied all over the body, acting like an invisible shield against bugs. Not only practical but also an early form of skincare!

Other tribes had their own secret sauces. In North Carolina, the scarlet root was a prized plant. John Brickell wrote it “has the Virtues to kill Lice, and suffer none to abide in their Heads.” Again, bear’s oil serves as the mixing agent, transforming plants into potent repellents.

Similarly, the Cherokees harnessed Golden Seal for the same purpose, mixing it with bear grease. These ointments weren’t just bug repellents; they were part of medicine, ritual, and daily life.

Mint Family Magic: Pennyroyal and Dittany

Here’s a fun fact: the mint family wasn’t just popular for cooking. Early Americans used plants like pennyroyal and dittany to keep fleas, ticks, and horseflies away.

The Rappahannock Indians hung dried pennyroyal in their homes as bug deterrents. It wasn’t just folklore; these plants contain essential oils that bugs hate—nature’s own bug spray.

Colonial William Byrd even documented how pennyroyal juice prevented deer ticks, and dittany helped fend off horseflies. Can you picture bottles of freshly squeezed pennyroyal juice lined up in a colonial apothecary?

The Power of Animal Oils

Bear’s oil wasn’t just a carrier for plants; it was a powerhouse repellent all on its own. Various Native tribes swore by bear’s oil to protect against “every Species of Vermin,” notably mosquitoes and bugs alike.

In New England, people added fish oil, eagle fat, and raccoon grease to their insect-defense arsenal. William Wood noted that aside from repelling bugs, these oils shielded skin from sunburn—talk about multitasking!

So, before the headache of chemical sprays, it was these animal fats that formed a greasy barrier against mosquitoes, biting flies, and the worst of the insect world.

Smoke: Creating a Bug-Free Atmosphere

If you ever wondered why campfires are bug magnets but sometimes also repellents, early Americans knew the difference. Burning certain plants like flea banes (Erigeron species) produced smoke that sent fleas and gnats packing.

Samuel Stearns wrote: “The chief use of the flea banes is for destroying fleas and gnats, by burning the herbs so as to waste away in smoke.”

Archaeological digs back this up. In Florida, a large circular building surrounded by posts was found, with burnt corncobs and plants in smaller post holes—probably to create a continuous smoke screen.

This design likely kept flying bugs away during gatherings, proving early Americans understood an essential truth: smoke can be a powerful insect repellent when done right.

What Did All These Practices Have in Common?

These techniques shared three smart principles:

- Leverage nature: They used locally available plants and animals wisely.

- Combination therapy: Plants and animal oils often worked together to increase effect.

- Environmental control: They didn’t just treat bug bites; they tried to keep bugs away from living spaces through smoke and plant placement.

Today’s bug sprays owe a lot to these original ideas. Animal oils replaced by synthetic chemicals, plants replaced by extract formulas, but the concept? Consistent—create a barrier bugs can’t cross.

Could These Ancient Tips Work for You?

Curious about natural bug repellents? Try dried pennyroyal or a few drops of golden seal oil mixed with a carrier oil (never pure). Keep in mind, some plants can be toxic if used improperly, so don’t go wild.

Also, consider a smoke screen trick next camping trip—burn a bit of flea bane or sage. Your extended outdoor dining might just become bug-free heaven.

Next time a mosquito buzzes in your ear, you can appreciate early Americans’ resourcefulness. They didn’t just swat and hope; they engaged in nature-based warfare with plants, oils, and smoke. Makes you wonder—what modern convenience will kids find quaint in 400 years?

Source: Vogel, Virgil J. American Indian Medicine, University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.