After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum ceased to function as an arena for gladiatorial fights and gradually transformed into a site with diverse and practical uses. No gladiatorial combats were held there following the 6th century, marking the end of its original purpose.

Over the centuries, the Colosseum served as a garbage dump and a papal quarry, providing building materials like marble and stone blocks for significant Vatican structures such as St. Peter’s Basilica and the Lateran Palace. Many of the marble blocks that once adorned the amphitheater were stripped away and reused, which explains the current sparsity of marble at the site.

In addition to material extraction, the arena and its extensive underground spaces (hypogeum) found other practical uses. People filled the hypogeum with dirt to create vegetable gardens, stored hay, and even dumped animal dung. The vaulted chambers above hosted cobblers, blacksmiths, priests, glue-makers, and money-changers. During the 12th century, the Frangipane family turned the amphitheater into a fortress, showcasing its strategic importance beyond entertainment.

Local folklore and superstition arose around the Colosseum during its decline. It was sometimes mistaken for a temple to the sun, and necromancers reportedly used it for rituals at night.

Pope Sixtus V attempted to repurpose the Colosseum in the late 16th century by converting it into a wool factory with workshops and living quarters. However, this ambitious project was abandoned because of high costs after his death in 1590.

The Colosseum also suffered from metal scavenging during the Middle Ages. Iron and steel clamps binding the stones were pried out, leaving visible holes in the walls. Despite this, the structure remains mostly intact. Additionally, informal activities like soccer and other everyday uses left carved names and marks, signaling its integration into local life.

From around 1750, the Colosseum’s status shifted towards preservation. Authorities began securing it as a historic monument and initiating restoration efforts. Over time, it emerged as one of the world’s most famous tourist attractions, drawing visitors eager to witness its ancient grandeur.

- No gladiatorial fights occurred after the 6th century.

- Used as quarry, dump, fortress, gardens, and workshops post-Roman Empire.

- Pope Sixtus V’s wool factory plan was abandoned after 1590.

- Metal scavenging damaged the structure but didn’t destroy it.

- Preserved as a monument from the mid-18th century onwards.

- Became a major tourist attraction following restoration efforts.

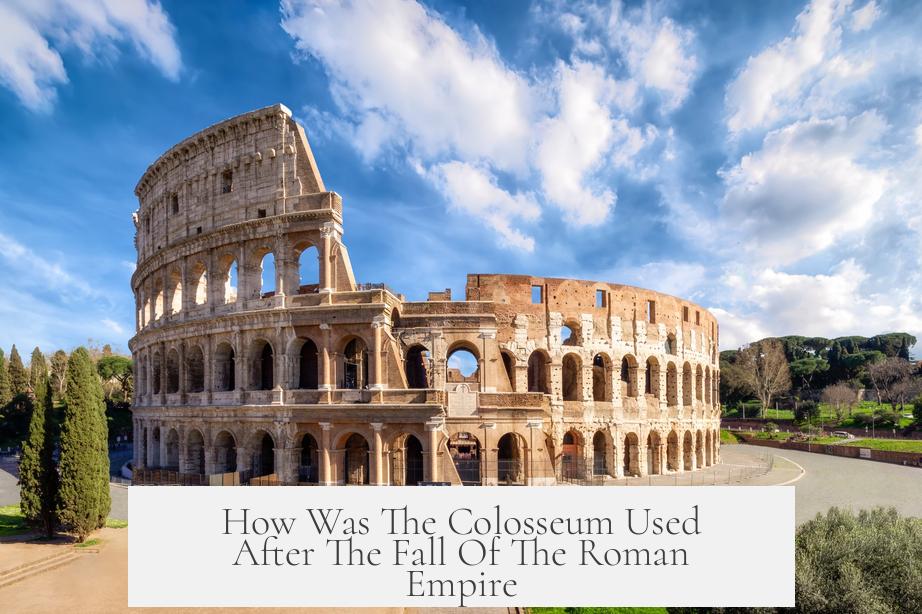

How Was The Colosseum Used After The Fall Of The Roman Empire?

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum did not continue as the magnificent arena of gladiatorial combat it once was. In fact, gladiatorial fights ended by the sixth century, marking the close of a brutal and thrilling era.

But what exactly happened to this vast amphitheater afterward? Was it repurposed as a political stadium, or did fights still echo in its grand stands? And when did it finally start drawing tourists rather than spectators of bloody contests?

Let’s unravel the fascinating journey of the Colosseum after the Empire’s collapse.

The End of Gladiatorial Spectacles

By the sixth century, the last gladiatorial fights took place in the Colosseum. Christianity had spread through the Empire, discouraging the violent spectacles once so treasured by Roman citizens. The gladiators’ bloodthirsty displays came to a definitive end.

Shortly afterward, the massive stone amphitheater began its slow decline. Stones were quarried from the walls; nature and neglect took their toll.

From Arena to Garbage Dump – A Dramatic Fall

Surprisingly, the mighty Colosseum was turned into a garbage dump. The once-celebrated centerpiece of Roman life became a huge rubbish pit. Dirt, rubble, and even animal dung filled the hypogeum (the underground part of the arena).

The grand vaulted passageways above didn’t escape neglect either. They became shelters for poor families, cobblers, blacksmiths, priests, glue-makers, and money-changers. It even served as a fortress for the Frangipane warlords in the 12th century. Imagine gladiators replaced by blacksmith clangs and cobbler hammers!

The Papal Quarry: Marble Theft on a Grand Scale

The marble that once gleamed on the Colosseum’s surface did not safely stay put. Over centuries, the Catholic Church repurposed much of the marble for its grand Vatican projects.

Stones and marble tops were carted off for landmarks like the Lateran Palace and St. Peter’s Basilica. Tour guides often note the odd lack of marble when you visit compared to the original Roman grandeur.

That’s right — the gleaming Vatican owes some of its sparkle to the Colosseum. The church essentially turned the amphitheater into its own quarry for hundreds of years.

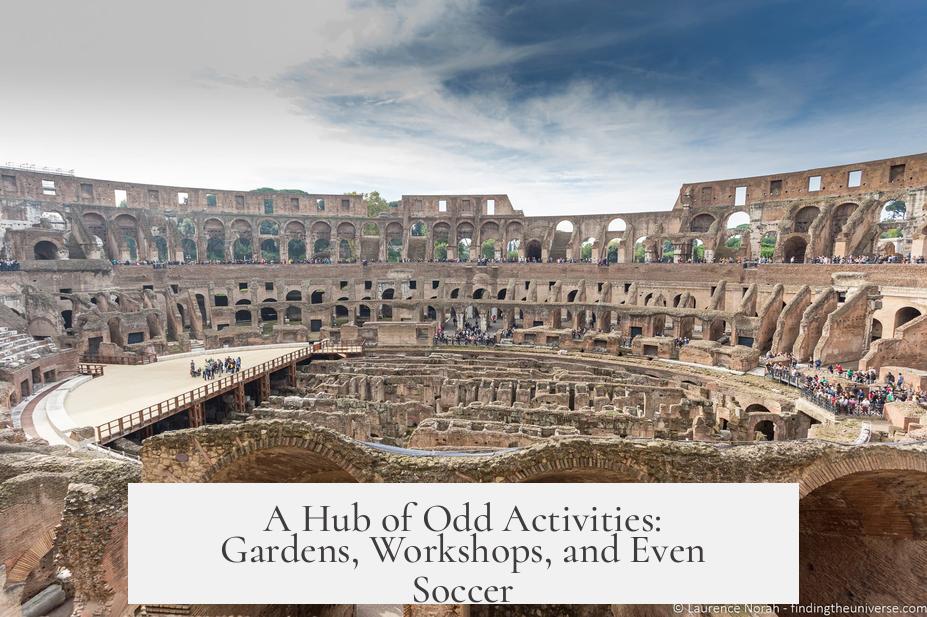

A Hub of Odd Activities: Gardens, Workshops, and Even Soccer

By the Middle Ages, the arena floor was layered with dirt, turning parts of the hypogeum into vegetable gardens and hay storage. Animal dung wasn’t spared either. The Colosseum’s vast spaces hosted a surprising variety of everyday activities.

- Sheltered guilds and trades inside the vaulted passages.

- Blacksmiths and cobblers set up shop.

- Money-changers counted coins amid crumbling stone.

- Necromancers performed eerie rituals, believing the crumbling ruins once served as a sun temple.

- Locals even played soccer there — apparently, a very historic pitch!

Yes, from a violent gladiatorial pit it shifted to a medieval multi-use space, unusual but alive with human activity.

Pope Sixtus V’s Wool Factory Dream

In the late 16th century, Pope Sixtus V had a bold plan: turn the Colosseum into a wool factory.

Workshops would occupy the arena floor, while upper stories became living quarters. Sadly, the pope died in 1590, and the project was abandoned due to its hefty price tag. Still, it shows the Colosseum’s adaptation potential — even if that particular vision fizzled.

The Colosseum’s Metal Theft and Structural Challenges

Another curious fact: the numerous little holes dotting the Colosseum’s walls date back to the Middle Ages. These were attempts to extract metal bars embedded within the stone, originally used by Romans to hold blocks firmly in place.

People chipped away stone just to get at these bars. The Colosseum’s resilience is remarkable — despite centuries of stone theft and natural disasters like earthquakes, it’s still standing.

When Did The Colosseum Become A Tourist Attraction?

By around 1750, appreciation for the Colosseum shifted dramatically.

Recognized as a monument, the arena was secured and efforts toward preservation began. It no longer served as a quarry or shelter but became a symbol of ancient Rome’s glory.

Tourists, historians, and artists flocked to see the colossal ruins — a transition from a decaying relic to a cherished landmark.

Today, millions visit annually. The Colosseum sparks wonder and curiosity about Rome’s past, gladiators’ lives, and architectural genius.

So, Were Fights Still Held? Was It Used Politically?

After the fall, no formal gladiatorial battles remained. The Colosseum did not become a political stadium in any traditional sense. Instead, it morphed through many practical and often humble uses — from garbage dump to workshop hub, to fortress, and even mysterious night haunt.

Political use, in the sense of organized events or speeches characteristic of the Empire’s heyday, vanished. The arena’s function shifted from spectacle to survival, echoing Rome’s own transformation.

What Can We Learn?

The Colosseum’s post-Empire saga reveals resilience and adaptability on both human and architectural levels.

From bloody combats gone silent to its transformation into a dumping ground, fortress, garden, workshop, and tourist magnet, the Colosseum embodies layers of history.

Next time you visit, ask yourself:

- Can you spot the scars of marble theft?

- Do you imagine the cobblers and blacksmiths working inside the ancient vaults?

- Does the echo of cheers now feel like a whisper of the past?

The Colosseum is more than a monument; it’s a living archive—a testament to Rome’s shifting fortunes and the human need to repurpose and find meaning in ruins.

How does this change your view of the iconic structure? Was it just a grand arena, or a versatile survivor of history’s twists and turns?