The story of the Green Children of Woolpit originates from medieval English folklore, documented in historical chronicles and later compiled by folklorists such as Katharine Briggs. Briggs includes the narrative in her works Folk Tales of Britain and An Encyclopedia of Fairies, noting the tale as one of the “curiously convincing and realistic fairy anecdotes” found in medieval records.

The legend describes two children with green-hued skin appearing in the village of Woolpit, speaking an unknown language. Over time, these children adapted to their surroundings. Though the exact origins remain unclear, the story was preserved because of its compelling nature and repeated retellings across generations.

Folklore often thrives on narratives that feel plausible and captivating. When many people share similar stories, the collective memory strengthens the legend’s believability. However, accepting one legend fully would imply accepting a wide range of supernatural phenomena, ranging from fairies to dragons. This highlights the challenge of distinguishing folklore from verified history.

Folklorists like Briggs approach such stories with analytical neutrality. Their role is to understand why and how communities tell these tales, not to confirm or deny the supernatural claims within them. They caution against taking legends literally but emphasize their cultural and narrative value. These stories endure because they entertain, engage, and reflect human imagination.

Concerning the Green Children, no verifiable evidence confirms their actual existence. It is unnecessary to assume their historical reality to explain how the story entered print or local tradition. The simplest explanation is that this tale emerged as an intriguing legend, passed through oral storytelling until recorded in texts.

Some individuals continue to believe in the factual existence of the Green Children. Such persistence in belief, despite skepticism, interests folklorists as it shows the power of narrative in shaping cultural memory and identity.

- The Green Children story originates from medieval folklore and is documented by Katharine Briggs.

- Legends survive because they are engaging and widely retold.

- Folklorists analyze stories without insisting on their literal truth.

- There is no proof the Green Children were real; the tale likely arose as a legend.

- Belief in the story persists, illustrating folklore’s cultural impact.

The Green Children of Woolpit: Where Does the Story Come From?

The story of the Green Children of Woolpit originates from medieval England and appears primarily through the meticulous work of British folklorist Katharine Briggs. Briggs compiled various versions of this curious tale in her respected works, including Folk Tales of Britain and An Encyclopedia of Fairies. These books serve as key sources for anyone interested in the tale’s origins and its intriguing persistence over centuries.

So, what exactly is this story? Two mysterious children, found in the village of Woolpit in Suffolk, reportedly emerged from underground tunnels. Their skin was green, and they initially spoke an unknown language. Over time, the boy sadly died, but the girl adapted to life above ground, eventually losing her green hue and explaining they came from a submerged, twilight land called Saint Martin’s Land. Fascinating? Absolutely. But let’s dig deeper into where the story itself comes from.

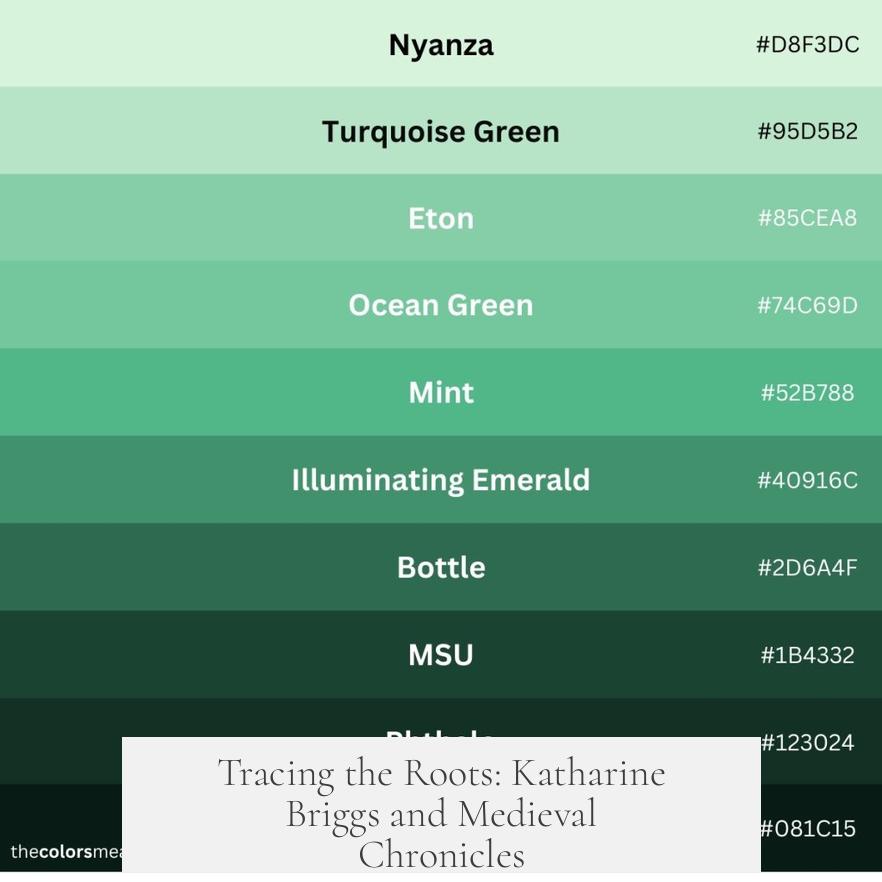

Tracing the Roots: Katharine Briggs and Medieval Chronicles

Katharine Briggs is essential to understanding this legend. She doesn’t merely recount the tale; she analyzes it. In her commentary, she calls the Green Children story “one of those curiously convincing and realistic fairy anecdotes occasionally found in medieval chronicles.” That means the story not only survived oral tradition but gained enough traction to be included in historical records from that era. Still, this inclusion does not prove the legend’s factualness but does show its resonance with people of the time.

This tale’s longevity points to its power as an engaging narrative, not as a piece of historical fact. Communities pass on stories that thrill and explain the unexplainable. Why? Because stories help us grapple with mystery and difference, especially in times when scientific understanding was limited.

Why Legends Like This Last: The Power of Storytelling

Legends aren’t just old stories—they survive because they’re convincing. People hear tales of the green children and their green skin and want to believe. When multiple people retell similar versions, the story feels authentic, even if it bends reality. This magical touch makes stories sticky, embedding in collective memory like superglue.

But here’s a puzzle: if we start believing every legend literally, we must accept a wide spectrum of supernatural beings—mermaids, trolls, dragons, gremlins, and countless others. This flood of fantasy becomes overwhelming and conflicts with rational understanding.

The Folklorist’s View: Not Proof, but Interpretation

Katharine Briggs, and folklorists generally, steer clear of taking these stories as literal truth. Their role is clear: to understand what these stories tell us about the people who told them. It’s not about proving or disproving fairy tales or magical beings.

Folklorists caution against accepting legends as realistic worldviews. Instead, they examine why such stories emerge. What fears, hopes, or values do they reflect? The Green Children story, with its eerie details and otherworldly features, reveals medieval England’s fascination with the unknown.

It’s worth mentioning that such stories thrive because they captivate. People love thrilling tales that stretch the mind. These stories often make it into books and official records simply because they entertain and provoke curiosity.

So, Did the Green Children Really Exist?

Here’s the critical question many ask. No one can confirm that the Green Children were real. There’s no solid historical evidence beyond stories recorded centuries ago. The tale might have been inspired by something real, like strangers from distant lands or people with medical conditions causing skin discoloration, but that is pure speculation.

Does their actual existence matter to the story’s power? Not really. The legend could have emerged simply because people like to tell intriguing stories. It makes sense to view it as folklore, not fact. The tale persists because it’s compelling, not because it’s verified history.

Interestingly, some people keep believing in the Green Children as historical figures. For folklorists, this is more than curious—it’s a window into how human belief works. People want to hold on to the enchanting possibility that there’s more to the world than meets the eye.

What Can We Learn From This Legend Today?

Stories like the Green Children of Woolpit remind us of the power of myth and narrative in shaping culture. They challenge us to ask questions: Why do people tell certain stories? What do those stories say about their world? And how do we separate fact from folklore responsibly?

If you want to explore this further, look at Katharine Briggs’ works or historical chronicles from medieval England where this story first appeared. You’ll find a treasure trove of material that blends mystery, psychology, and culture.

Next time you hear about the green-skinned children from Woolpit, consider the story’s origin and what it reveals about human storytelling. It’s a weird, wonderful, and cautionary tale about how legends are born and why they live on.

In Conclusion

The Green Children of Woolpit story springs from medieval England, preserved through works by Katharine Briggs and medieval chronicles. It’s a legend crafted because it’s engaging and convincing, rather than an assured reality.

Folklorists teach us to appreciate such narratives for what they reveal about belief and culture, not to accept them as literal truths. So, whether you find the tale thrilling, puzzling, or fanciful, it continues to inspire fascination in the human imagination.