The English swapped the pike for the billhook due largely to the unique conditions of the Battle of Flodden in 1513. While the pike was the dominant formation weapon in Europe, its effectiveness depended heavily on unit cohesion and favorable terrain. At Flodden, difficult terrain caused the Scottish pike formations to break apart, allowing English soldiers armed with billhooks—a weapon better suited for individual combat—to prevail in fragmented fighting. However, this shift was not based on the superiority of the billhook in normal warfare. The pike remained the preferred weapon for centuries, and the billhook’s prominence was a short-lived response to very specific tactical circumstances rather than a deliberate, widespread switch.

The battle of Flodden is often viewed as a fluke in military history because the English success with the billhook resulted from extraordinary conditions. The Scottish army mostly relied on pikes, long spears up to 18 feet, arranged in tight formations that demanded strict unit cohesion. This cohesion was vital since pikes were highly ineffective outside these formations. Individually, soldiers wielding long pikes were vulnerable because the weapon was unwieldy and difficult to use in close combat situations without the protective mass of their unit.

At Flodden, the Scots faced a challenge when forced to descend Braxton Hill and cross a marshy area not visible beforehand. The wet, uneven terrain caused their tightly packed pike formations to falter as soldiers lost footing. Once broken, the unit could not maintain the effectiveness of the pike. The English troops, carrying billhooks, exploited this situation. Billhooks were shorter polearms with hooked blades derived from agricultural tools. Unlike pikes, billhooks excelled in close quarters and individual combat, offering a dynamic advantage when formations disintegrated.

Despite the success of the billhook at Flodden, it is crucial to place this event in context. The English victory over the pike formations was largely due to terrain and tactical misfortunes, not an inherent superiority of the billhook. In other parts of the battlefield where the Scottish pike formations remained intact, they performed well. The English cavalry even had to intervene decisively to assist a faltering English flank, indicating the battle was complex and not a simple weapon vs. weapon contest.

Historical records show that after Flodden, the Scottish government banned a weapon called the Jedburgh Stave—a long polearm similar in use to the pike—which was blamed for poor performance. However, they made no such moves against the pike itself. Meanwhile, across Europe, the pike continued its dominance as infantry’s primary defensive and offensive tool for several centuries. The English also transitioned from traditional bills and bows to a combination of pikes and firearms over time, signaling confidence in the pike’s battlefield role.

George Silver, an Elizabethan fight master, praised the English bill as unmatched in individual combat, highlighting its strength in tangled fighting situations. However, this did not translate to superiority in regular massed battles with disciplined pike infantry. The billhook’s effectiveness in the Battle of Flodden was an exception caused by disrupted formations, which normally rendered the weapon ineffective as a main infantry arm.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Pike’s Strength | Formations, unit cohesion, reach, effective in close order combat |

| Pike’s Weakness | Useless individually, unwieldy, vulnerable if formations break |

| Billhook’s Strength | Effective in individual combat and broken formations |

| Billhook’s Weakness | Less effective in formation battles versus pikes |

| Flodden Impact | Scottish pike formations broke in marsh, English bills exploited |

| Post-Flodden Outcome | Pike remained dominant; billhook’s prominence was a battlefield quirk |

In summary, the English’s temporary switchover from pikes to billhooks after Flodden does not indicate a permanent or strategic replacement based on weapon superiority. The conditions at Flodden were unique and unlikely to repeat. The failure of the Scottish pike formations was due to terrain and loss of cohesion rather than an inherent billhook advantage. The pike stayed relevant, shaping infantry tactics for decades after.

- The Battle of Flodden’s terrain disrupted Scottish pike formations.

- The billhook excelled in individual and broken-formation combat.

- The pike was ineffective without tight unit cohesion.

- English billhook success at Flodden was circumstantial, not strategic.

- Post-Flodden, pikes remained the dominant infantry weapon in Europe.

Why Did the English Swap Out the Pike for the Billhook? The Fluke of Flodden and the Tale Behind the Trade

Answer upfront: The English didn’t really swap the pike for the billhook because the bill was a superior weapon. In fact, the famous Battle of Flodden, where English billhook-armed soldiers defeated Scottish pikes, was mostly a one-in-a-million quirk of battlefield conditions rather than a clear proof that bills outmatched pikes. The pike’s reign continued long after, and the English gradually adopted pikes and firearms, sidelining the bill. Flodden was a fluke – a perfect storm of bad terrain and brilliant English tactics – rather than a strategic revolution in weapon choice.

Let’s unpack this curious piece of weapons history. Why did one of the most iconic pole weapons in England, the billhook, linger long after its continentally famous cousin, the pike, seemed like the “modern” choice? And did the Battle of Flodden really prove anything decisive about their battlefield efficacy?

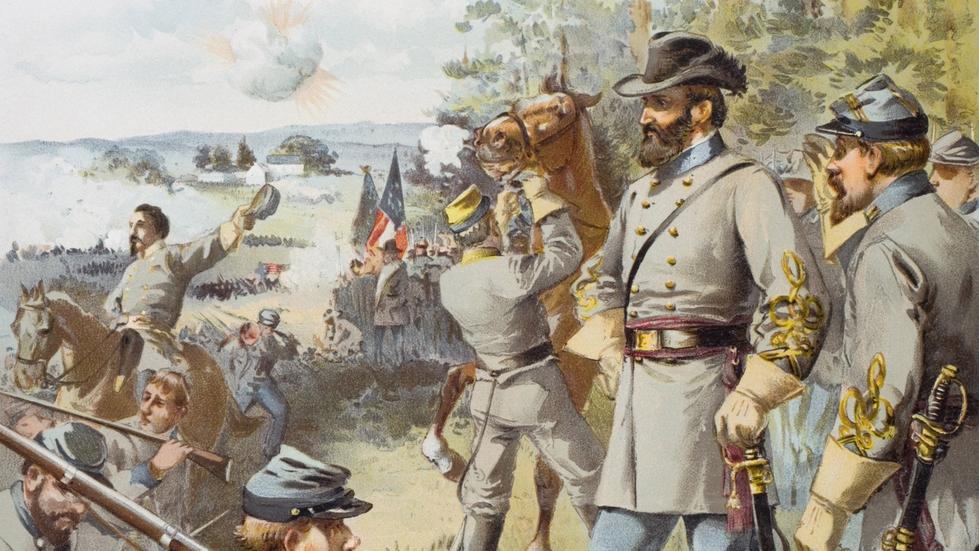

The Battle of Flodden: A Glorious Fluke, Not a Formula

First, picture the Battle of Flodden, fought in 1513. The Scots had what looked like a winning formula. Their army was “modern” by 16th century standards—a solid artillery train, infantry armed with pikes reflecting continental European military trends, and leadership shaped by Renaissance ideas and French military theories. All the boxes ticked for a Scots victory.

Meanwhile, the English forces, led by Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, seemed almost stuck in a past era. They wielded bills (a type of hooked polearm) and bows — weapons that on the continent had pretty much disappeared from major battles. Their artillery was modern too, but mostly leftover bits since Henry VIII had shipped the big guns off to France.

This doesn’t sound like a recipe for English triumph, does it? Yet the English won, impressively.

Terrain, Tactics, and Timing Tripping Up the Pikes

The key to the Scots’ defeat wasn’t that the billhook magically trumped the pike. Instead, tough terrain and clever English tactics did what weapon superiority alone could not. As the Scots marched down Braxton Hill to meet the English, the ground beneath their feet turned nasty. A hidden marsh from hill runoff looked solid but was actually a quagmire waiting to swallow men and break formations.

And here lies the pike’s Achilles heel: it demands strict unit cohesion. Pike formations are vast walls of 15 to 18-foot spears pointing outwards, creating an impenetrable forest of steel—but only if tightly packed. Once cohesion breaks, these tall poles become dead weight; individually, a pike is not just useless but hazardous to wield.

Stumbling soldiers in the muddy marsh smashed apart the Scottish pike phalanxes. Suddenly, these great spears were nothing but long sticks in the hands of disorganized men. This shattered formation became easy pickings for the nimble English troops wielding bills, weapons dubbed “without peer for individual combat” by fighting expert George Silver.

Why Did the Billhook Work So Well Then?

The billhook was a clever piece of gear: a hybrid of a spear and an axe with a hooked blade, roughly 5 to 6 feet long. Built for chopping, hooking, and thrusting, it excelled in close combat and didn’t need a formation wall to be effective. Its compact size gave the English troops a flexibility the pike lacked in broken terrain.

At Flodden, this versatility shone. The Scots’ tightly knit pike blocks collapsed into fragmented skirmishes, where individual skill and weapon agility mattered. English soldiers with bills used hooks to pull riders off horses, chop apart an opponent’s pike shaft, or thrust with deadly precision. The billhook’s design naturally suited breaking up and fighting within the chaos caused by terrain and tactics.

Was the Billhook Superior to the Pike? Not Quite.

While the bills did well at Flodden, this battle is more the exception than the rule. Scottish pikes held strong in other parts of the field; English cavalry had to intervene to prevent a collapse on the English right flank. Under normal conditions, massed pikes had proven victorious repeatedly on the European battlefield. Pike formations, often supported by musketeers or arquebusiers, dominated until firearms and artillery evolved sufficiently to render dense pole schemes obsolete.

In fact, contemporaneous military thinkers and later historians agree: the pike was the superior choice for battlefield dominance in open and stable environments. It was only terrain, disorganization, and a pinch of English cunning that gave the billhook a starring role at Flodden.

Did the English Embrace the Billhook After Flodden? History Says Nope

Contrary to what you might expect, the English didn’t rush to swap out their pikes for bills after Flodden. While the bill remained popular domestically for centuries, especially in militias and among archers, the military trend was unmistakably moving toward pikes and firearms. Eventually, the English replaced their “bills and bows” with continental-style pike and shot units.

The Scottish reaction was similarly practical: they banned the Jedburgh Stave—a weapon that underperformed at Flodden—but left pikes untouched. The pike’s dominance continued, emphasizing the battle as an anomaly rather than a new standard.

When Weapon Choice Meets Reality: What Does Flodden Teach Us?

So, what’s the takeaway for history buffs and weapon enthusiasts? The English swapping pikes for bills? Never really happened on a grand strategic level due to Flodden.

Flodden teaches one big lesson: context is king. Even the finest weapon can fail if the ground shakes it. The smartest army wins not just with superior gear but with terrain mastery, discipline, timing, and daring leadership. You can have the best equipment, but if the land underfoot turns to mud, that advantage can vanish.

Plus, it nudges us to think beyond simple “better weapon” narratives. Battles are messy, unpredictable, and sometimes hinge on flukes. The English billhook had its moment, sure—but it wasn’t a wholesale game-changer. Instead, it complemented conditions smartly exploited by commanders.

Practical Thoughts for Weapon Aficionados and Re-enactors

- If you’re intrigued by polearm combat, consider the billhook’s versatility compared to the pike’s discipline requirement.

- Training with a pike demands focus on maintaining formation and synergy; break formation and the pike becomes a liability.

- The billhook’s shorter reach and multiple attack vectors make it ideal for messy, close quarters or rough terrain, just as in Flodden’s marshy fields.

- For historical reenactors, understanding terrain impact can shape how battles and drills are practiced effectively.

Conclusion: Billhooks, Pikes, and the Mastery of the Battlefield

In short, the English didn’t swap the pike for the billhook because the bill was clearly better. The famous Battle of Flodden was a surprising combination of geography, ground softness, and tactical skill that allowed the billhook to shine briefly. The pike remained Europe’s dominant polearm for centuries. Eventually, both were eclipsed by firearms. But Flodden reminds us that weapon choice never happens in a vacuum; it depends on leadership, terrain, and a bit of battlefield luck.

So next time you wonder why England held onto the billhook when Europe was headlong for the pike, remember: sometimes history’s weird quirks shape weapon trends more than simple logic. Flodden was a fluke, not a revolution.

Why did the English find the billhook effective at the Battle of Flodden?

The marshy ground at Flodden broke Scottish pike formations. Without cohesion, pikes became useless. The billhook was better suited for individual combat and loose fighting, letting English soldiers exploit the broken Scottish lines.

Was the billhook considered superior to the pike in all battles?

No. The billhook only excelled at Flodden due to broken formations and bad terrain. Under normal conditions, pikes were superior and remained the top formation weapon in Europe for centuries.

Why couldn’t Scottish pike formations hold their ground?

They had to cross marshy terrain that seemed solid but was treacherous. Soldiers lost footing, unit cohesion collapsed, and the long pikes became liabilities instead of weapons.

Did the English continue to use the billhook after Flodden?

No. The billhook was largely replaced by pikes and firearms. Flodden was an exception, not the start of a new trend in weaponry.

How did commanders view the effectiveness of the billhook against pikes?

English leaders saw the billhook as a great weapon for individual fighting but recognized it could not replace the pike’s strength in tight formations. The pike’s dominance in massed battle remained uncontested.