Rosa Parks’ refusal to yield her seat was not a prearranged act planned to launch the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but it was deeply connected to a larger context of activism and coordination within the Black community. She acted out of personal conviction but was informed by ongoing organized efforts for civil rights. While the boycott itself was highly organized and based on earlier precedents, Parks’ specific moment was spontaneous in outcome but framed by sustained activism.

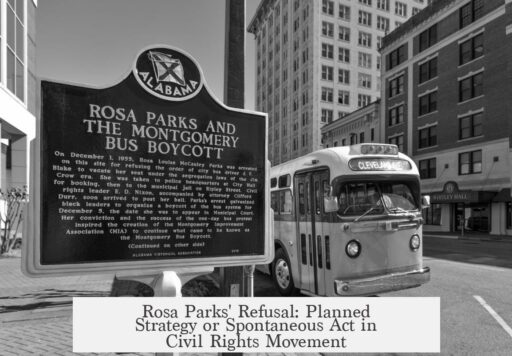

Rosa Parks’ refusal on December 1, 1955, stands as a pivotal moment in civil rights history. However, this action was not a carefully scripted event set up to start the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Parks was a respected local activist and NAACP secretary for over a decade. Her motivation came from years of experiencing injustice and her well-known community role. She later stated, “The only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Despite the spontaneous element of her arrest, the Montgomery Bus Boycott had deep roots in prior activism and coordination. Two years earlier, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a similar bus boycott successfully protested discriminatory seating policies. Local leaders there discovered that 80% of bus riders were Black and leveraged that economic power via an eight-day boycott, aided by a community carpool system. This precedent provided a blueprint for Montgomery activists.

- Reverend T.J. Jemison, a Baton Rouge boycott leader, influenced civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr.

- The success of Baton Rouge’s boycott informed Montgomery’s later organizational strategies.

In Montgomery, activists including Jo Ann Robinson, head of the Women’s Political Council, had been advocating for bus reforms and had warned the city in 1954 about potential boycotts planned by local organizations. This demonstrated an existing buildup of organized protest efforts against bus segregation.

Following Parks’ arrest, local activists swiftly organized. On December 5th, leaders from the NAACP, Women’s Political Council, and Black churches convened. They called for a one-day bus boycott, attracting 90% participation from Black riders. That evening, the community leaders resolved to extend the boycott and formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as its leader, guiding a sustained boycott lasting 381 days.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Precedents | Bus boycott in Baton Rouge (1953) informed Montgomery’s strategy. |

| Activism Background | Rosa Parks was NAACP secretary and a community activist. |

| Organized Planning | Warnings about boycott surfaced in 1954; rapid coordination post-arrest. |

| Boycott Duration | Lasted 381 days with coordinated leadership under MIA. |

Parks was not trying to provoke an arrest. She boarded the bus simply to go home and refused to give up her seat, an act borne out of weariness with systemic injustice. Her choice had immense ramifications due to the existing civil rights groundwork and community readiness for protest. Her arrest became a catalyst, but not an orchestrated trigger.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott’s success required extensive cooperation and planning beyond just Parks’ arrest. It reflected a complex mix of spontaneous individual acts and long-term movement preparations. It’s important to note that no one could predict the boycott’s scale, the resistance it faced, or its national impact at the moment of Parks’ arrest.

This tells us:

- Rosa Parks’ act was both personal and informed by activism.

- The boycott was based on previous protests and significant local organizing.

- Black community leaders had planned for potential coordinated action prior to Parks’ arrest.

- The lasting boycott combined grassroots activism, economic leverage, and leadership.

- Spontaneity and planning coexisted, highlighting the complexity of social movements.

Was Rosa Parks’ Refusal to Yield Her Seat a Planned and Coordinated Effort?

Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat was both a deeply personal act of defiance and part of a broader, informed movement with roots in legal and community activism. It wasn’t a mere accident or a spur-of-the-moment rebellion, but also wasn’t a scene from a secret script penned behind closed doors. Parks stood up—or rather, stayed seated—at a complex crossroads of individual courage and collective strategy.

Let’s untangle this historical weave.

Context: The Groundwork Before Montgomery

Before Parks made history in Montgomery, others had already tested the waters. The bus boycott in Montgomery didn’t emerge from thin air. It followed in the footsteps of the Baton Rouge bus boycott in 1953. This earlier protest highlighted a simple but powerful truth: Black riders made up 80% of bus patrons and could leverage that for change.

In Baton Rouge, local Black leaders—including the influential Reverend T.J. Jemison—drew up plans to challenge segregated seating. That boycott lasted eight days and introduced carpooling systems to keep the protest economic but practical. The outcome was a compromise that began chipping away at segregation on buses.

When MLK Jr. visited Baton Rouge in 1953, he consulted with leaders like Jemison. These conversations helped shape the strategies that would later define Montgomery’s movement. So, behind the scenes, groundwork and networking were well underway.

Rosa Parks: More Than Just a Seamstress

Often portrayed as an ordinary woman pushed to the edge, Rosa Parks was anything but unprepared. Her twelve years as Secretary of the Montgomery NAACP chapter gave her a deep understanding of civil rights activism. She wasn’t testing the waters to provoke arrest, as she famously said, “I did not get on the bus to get arrested; I got on the bus to go home.”

Yet, Parks was no stranger to the risks involved. She had received community activism training at the Highlander Folk School and had already been working on desegregation issues. Parks’ refusal was both a spark and the product of years of frustration and organized resistance.

Her simple statement, “The only tired I was, was tired of giving in,” reflects her personal resolve intertwined with a clear awareness of the injustice she confronted.

Signs of Pre-Planning: Hints in the Public Sphere

Looking at the months before Parks’ arrest, we find evidence that bus boycotts were a hot topic in Montgomery. Jo Ann Robinson, leader of the Women’s Political Council, warned city officials in 1954 about the brewing discontent. She explicitly mentioned discussions about a city-wide bus boycott among over twenty-five local groups.

This reveals that the boycott was no sudden movement—it simmered under the surface, fueled by organized entities ready to act when the right moment came.

The Spark and the Fire: Immediate Community Response

The day after Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, community leaders from the NAACP, the Women’s Political Council, and local churches, including a young Martin Luther King Jr., met to plan a reaction. They agreed upon a one-day boycott for December 5th. The results were striking: 90% of Black bus riders stayed off the buses, sending a loud message.

That evening, seizing the moment, leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and chose MLK Jr. as its leader. Their mission? To continue the boycott indefinitely. What followed was a year-long campaign of coordinated action—carpools, legal battles, rallies—that kept the fire alive and focused.

A Blend: Spontaneity Meets Strategy

It’s tempting to see Parks as either a lone hero or a planned provocateur. Actually, she was both fed up and informed, spontaneous and strategic. The boycott didn’t emerge from thin air on December 1, 1955 — it built on years of warning, organizing, and precedent.

This blend of readiness and genuine passion is typical of social movements. Rosa Parks was not an accidental symbol. She was a respected activist whose choice to remain seated turned into a catalyst because of the ongoing groundwork laid by community leaders.

The Unpredictable Magic of History

Despite all the planning and organizing, no one could have predicted every twist. Nobody knew Parks would get arrested that day, or that the majority of Black riders would fully commit to the boycott. The violent backlash, national media attention, and ultimate legal victories—the whole domino effect—were impossible to foresee.

This mix of deliberate action and unpredictable outcomes is what gives the boycott its lasting power and lessons.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Understanding the layered reality behind Rosa Parks’ refusal teaches crucial lessons about change. Major victories rarely happen from a single courageous act alone. Often, they grow from community efforts and repeated calls for justice, with well-organized groups ready to transform personal courage into collective power.

What if history had only celebrated Parks’ seating act without crediting the people and planning behind it? It’s important to recognize that lasting progress comes from millions of small, often invisible seeds being planted.

Practical Takeaways

- Individual Actions Can Spark Change: Like Parks, standing firm matters, even when the system seems stacked against you.

- Community Organizing Amplifies Impact: Collective action—like the MIA’s coordination and the Women’s Political Council’s groundwork—turns sparks into a blaze.

- History Is Complex: Real-life change involves struggle, negotiation, setbacks, and hope—not simple stories.

- Awareness Empowers: Knowing what happened before and after Parks’ act helps us appreciate the layers behind social change.

In sum, Rosa Parks’ refusal to yield her seat was part personal protest and part strategic movement-building. It’s a beautiful example of how history is rarely a solo script—but a collaborative production with many actors, rehearsals, and unexpected moments.

So the next time you hear the phrase “the woman who sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” remember: she sparked a fire already kindled by many. And that’s precisely why it burned so bright.